Larry Swedroe is quite literally “the perfect guest” for our “Investing Legends” series as he’s in my opinion the most prolific investment writer and researcher of our time.

Whenever I follow his feed on Twitter (@larryswedroe), I notice new research supported articles being published or a new book being announced.

It just so happens that Larry has published a new book Your Essential Guide to Sustainable Investing, which is packed with the theory and empirical findings from more than 5 dozen papers.

I’m traveling at the moment, so it is a book I plan on reading when I return home.

However, I can tell you as a reader of five of his previous books, I know in advance I’ll enjoy it.

Larry’s Your Complete Guide to Factor Investing and Reducing the Risk Of Black Swans are two of my favourite investing books of all-time.

I thought I’d try a unique style of interview with Larry where I try to combine his knowledge and wisdom of investing with his love for baseball.

Listening to some of his previous podcasts, he discloses he almost worked for the New York Yankees.

Although in a parallel universe Larry may have enjoyed a distinguished career in baseball, we as investors should be thrilled he focussed his time and energy on topics such as factor investing, investor psychology and portfolio optimization.

In this comprehensive interview we’ll cover three investing questions with a baseball theme and then hear from Larry about his latest book.

Larry Swedroe: Multi-Factor Investing, Behavioural Finance and All Weather Portfolios

About the Author & Disclosure

Picture Perfect Portfolios is the quantitative research arm of Samuel Jeffery, co-founder of the Samuel & Audrey Media Network. With over 15 years of global business experience and two World Travel Awards (Europe’s Leading Marketing Campaign 2017 & 2018), Samuel brings a unique global macro perspective to asset allocation.

Note: This content is strictly for educational purposes and reflects personal opinions, not professional financial advice. All strategies discussed involve risk; please consult a qualified advisor before investing.

Source: Rational Reminder on YouTube

These asset allocation ideas and model portfolios presented herein are purely for entertainment purposes only. This is NOT investment advice. These models are hypothetical and are intended to provide general information about potential ways to organize a portfolio based on theoretical scenarios and assumptions. They do not take into account the investment objectives, financial situation/goals, risk tolerance and/or specific needs of any particular individual.

How To Build An All Season Portfolio

Furthermore, can you think of a specific season and baseball team you followed that displayed all-weather characteristics to win the World Series?

At Buckingham Strategic Wealth our investment strategy is based on three key principles.

First, markets are highly, though not perfectly, efficient. That leads to the conclusion that active management is the loser’s game. Investors should thus use only index funds, or other funds that use systematic fund construction rules to gain access to unique sources of risk and return.

Second, if markets are efficient than you should also believe that all unique sources of risk have similar risk-adjusted returns, not similar returns, but similar risk-adjusted returns, NOTING THAT RISK IS NOT JUST VOLATILITY, BUT ALSO ILLIQUIDITY AND FAT TAIL RISK.

Third, If all unique sources of risk have similar risk-adjusted returns than Portfolios should be diversified across as many unique/independent sources of risk and return as you can identify that meet the criteria of persistence, pervasiveness, robustness to various definitions, implementability (meaning survives transactions costs) and have intuitive risk- or behavioral-based explanations that provide reasons for believing that the premium should persist in the future.

We prefer risk-based explanations because risk cannot be arbitraged away, although popularity, and the resulting cash flows can reduce premiums. However, we are willing to accept behavioral explanations because there are what are called limits to arbitrage. The cost of shorting can be high and the losses are unlimited.

In addition, The charters of many institutions prohibit shorting. These limits, as well as the tendency for Human Behavior to remain unchanged, allow anomalies, such as the poor performance of small growth stocks with high investment and low profitability, to persist.

The problem is that traditional portfolios are dominated by single risk: market beta.

Typical Portfolio: 60% Stocks/40% Bonds

Equity Volatility 20%

Bond Portfolio (4-5 Year Average Maturity) Volatility 5%

Equity Risk: 60 x 20 = 1200 + Bond Risk: 40 x 5 = 200

Total Risk: 1200 + 200 = 1400

Percentage Equity Risk: 1200/1400 = 86%

As you can see, a typical 60/40 portfolio, one that invests in total market funds, has about 86% of its risk in the single factor of market beta.

TO REPEAT, if all risky assets have similar risk-adjusted expected returns, the prudent strategy is one of broad diversification, not concentration of risk in one single factor, U.S. market beta.

That means That diversifying risks away from that single risk, adding exposure to other factors such as size, value, profitability/quality and momentum.

My book Reducing the Risk of Black Swans shows how increasing your exposure to those factors while simultaneously reducing your exposure to market beta has historically reduce tail risk and improved Sharpe ratios-you can hold less equity risk because the equities you hold have higher expected returns.

You can further improve the efficiency of the portfolio by considering adding other assets with unique risk such as: reinsurance (funds like SRRIX and XILSX); private credit which has large illiquidity premiums (interval funds like CCLFX and LENDX); long-short factor funds (like QSPRX and QRPRX); and other interval funds that invest in assets like life settlements, drug royalties, and litigation finance (funds like NICHX and CELFX).

Each of these investments has low to no correlation with the risks of stocks and bonds, and they also come with significant risk premiums to compensate for their unique risks.

By adding assets with unique risks your portfolio will be better able to survive whatever the economy environment, be it high (low) growth with high (low inflation).

Doing so allows you to build a “team” that won’t be the best performer in all environments, but it will greatly reduce the dreaded tail risk that can cause portfolios to fail.

Think of this type of portfolio as one of “risk parity”spreading its risks roughly equally across many unique sources of risk instead of concentrating it in one.

Again my Black Swan book shows how this can be accomplished.

You can also think of it the way a good GM of a baseball team puts his team together.

In baseball the teams that win the world series are not necessarily the ones with the best offense, defense or pitching, but a good balance of the three.

Source: Resolve Asset Management on YouTube (The investment performance results presented here are based on historical backtesting and are hypothetical. Past performance, whether actual or indicated by historical tests of strategies, is not indicative of future results. The results obtained through backtesting are only theoretical and are provided for informational purposes to illustrate investment strategies under certain conditions and scenarios.)

Multi-Factor Portfolios Best Practices

Q2) In your book The Complete Guide to Factor investing you identified four equity factors that drive returns in particular.

Value. Momentum. Quality/Profitability. Size.

Instead of seeking individual funds for each of these factors, I remember reading (in your orange factor book) that a more prudent way to invest would be to take a bottom up multi-factor approach.

Is this bottom-up multi-factor approach to pulling the levers of all four factors the equivalent of finding a baseball player who can hit for power, drive in runs, take a walk, bunt occasionally, steal bases and make spectacular plays out on the field?

What advantages specifically do multi-factor funds have over single factor funds?

Is there any baseball player (past or present) that best represents your ideal of a complete player who could do it all?

How a Multi-factor Portfolio is Constructed Matters

The CAPM was the first formal asset-pricing model. Market beta was its sole factor. With the 1992 publication of their paper, “The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns,” Eugene Fama and Kenneth French introduced a new-and-improved three-factor model, adding size and value to market beta as factors that not only provided premiums, but also helped further explain the differences in returns of diversified portfolios.

However, financial innovation didn’t end there. While the academic literature now contains more than 600 factors, there are only a relatively small number that have gained popularity, as they have been viewed as being persistent, pervasive, robust to various definitions, implementable (survive transaction costs), and have intuitive risk-based or behavioral-based explanations for why they should persist. In addition to the three Fama-French factors, we can add, momentum, profitability, quality and low beta/low volatility.

Note that while factor premiums are based on long-short portfolios (the value premium is captured by going long stocks with low prices to metrics such as book value, earnings and cash flow and going short stocks with high prices relative to those metrics), in practice, factor investing is typically implemented in a long-only framework.

Single-Factor or Multi-Factor Approach?

For investors who decide to strategically allocate to factor premiums, the question of how to most efficiently construct portfolios that provide exposures to these factors is critical. Is it better to create a portfolio using individual, single-factor components (thinking of them as “building blocks”)? Or, is it better to build a multi-factor portfolio from the security level (where scoring or ranking systems are used to select securities)? It should be intuitive that the latter approach, using multi-factor funds rather than single-factor funds (what is referred to as a bottom-up approach), is superior. One reason is that if you use the component approach, you will have one factor fund buying a stock (or group of stocks) while another factor fund will be selling the same stock (or group of stocks). For example, if a stock (or an entire sector) is falling in price, it might drop to a level that would cause a value fund to buy it, while a momentum fund would be selling the very same security. Investors would thus be paying two management fees and also incurring trading costs twice, without having any impact on the portfolio’s overall holdings. The unnecessary turnover could also lead to the realization of capital gains.

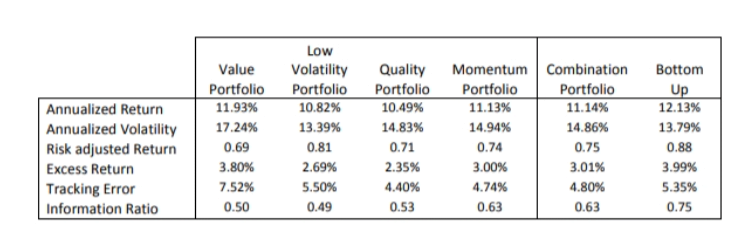

Jennifer Bender and Taie Wang, authors of the 2016 study “Can the Whole Be More Than the Sum of the Parts? Bottom-Up versus Top-Down Multifactor Portfolio Construction,” which appeared in a 2016 Special QES Issue of The Journal of Portfolio Management (link here), examined which of the two approaches is more efficient. The authors observed that the bottom-up (multi-factor) approach would seem to be a better one because the portfolio weight of each security will depend on how well it ranks on multiple factors simultaneously, while the approach combining single-factor portfolios may miss the effects of cross-sectional interaction between factors at the security level. The study used the equity factors of value, size, quality, low volatility and momentum, from which the authors built global portfolios from developed markets.

Bender and Wang found that the bottom-up portfolio returns were higher than any of the underlying individual component factor returns and higher than the combinations. Additionally, volatility of the bottom-up portfolio was significantly lower. For example, over the period from January 1993 through March 2015, the combination portfolio not only earned a lower return than the bottom-up portfolio (11.1 percent versus 12.1 percent), but it also exhibited higher volatility (an annual standard deviation of 14.9 percent versus 13.8 percent). The following table from their study summarizes Bender and Wang’s results.

They also found that “the bottom-up approach consistently produced better performance over the combination approach in all periods.” Bender and Wang concluded “there are, in fact, beneficial interaction effects among factors that are not captured by the combination approach. Both intuition and empirical evidence favor employing the bottom-up multifactor approach.”

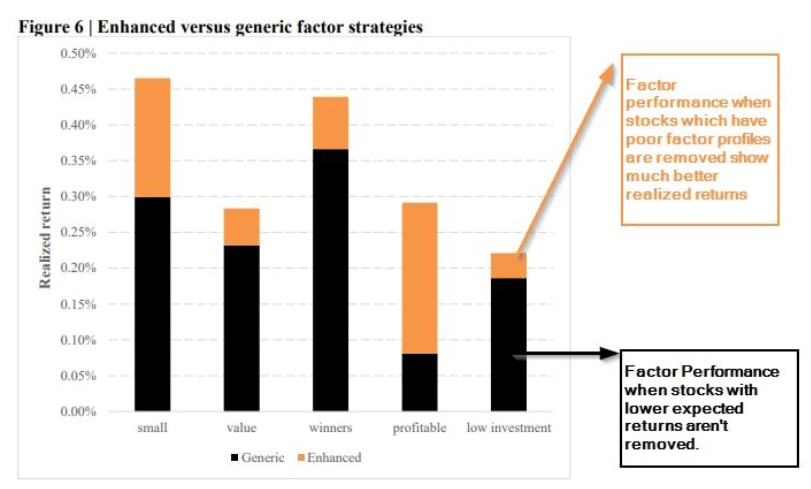

The latest support for the multi-factor approach comes from David Blitz and Milan Vidojevic, authors of the July 2018 study “The Characteristics of Factor Investing.” They built a characteristics-based multi-factor expected return model to qualitatively and quantitatively describe the returns of factor-based portfolios. This model enabled them to estimate the expected returns of each stock in the universe, at each point in time, and further to aggregate these expectations on a factor-portfolio level. Their data sample covers the period from June 1963 through December of 2017. The following is a summary of their findings:

- Single-factor portfolios, which are strategies that invest in stocks that score highly on one particular factor, are generally suboptimal because they ignore the possibility that these stocks may be unattractive from the perspective of other factors. Negative contributions from other factors cause these strategies to have a substantial weight in stocks with negative expected and ex-post realized market-relative returns. For example, a generic value strategy invests, on average, about 20 percent in stocks that are expected to underperform. While these stocks have attractive value characteristics, which contribute positively to their expected returns, their other factor characteristics are unattractive, and the negative contributions from these factors offset the positive contribution from value. Other generic factors display similar patterns.

- The return of generic factor strategies can be enhanced significantly by simply removing stocks that have lower expected returns than the market, based on their overall factor profile. Some stocks have such poor factor characteristics that their expected returns end up being lower than returns on Treasuries. By simply removing those stocks from the market portfolio ex-ante, the realized market return increases by 16 percent, in relative terms. Here’s the applicable table from their study.

- Return differences between factor portfolios in the small-cap and large-cap space, and between equally weighted and value-weighted factor portfolios, can also be explained by their model.

- The market portfolio itself suffers from a significant return drag caused by stocks with unattractive factor characteristics. The market portfolio is invested, on average, about 9 percent in stocks that have an expected return lower than the expected return on 10-year Treasury bonds. Removing such stocks from the market portfolio increases the equity risk premium by about 16 percent, in relative terms.

- Solely targeting the profitability premium and the size premium results in suboptimal results unless they take other factors, and, crucially, the price paid per unit of fundamental (book) value, into account.

Blitz and Vidojevic concluded that “a thorough understanding of how factor characteristics drive portfolio returns is the key towards successful factor investing.”

Summary

Both the logic and the evidence presented demonstrate that the way factor-based portfolios are constructed matters a great deal. Efficient portfolios are ones that are both designed from the bottom up and exclude stocks that have negative loadings on other factors to the extent they create a substantial drag on returns. Thus, returns of even single-factor portfolios can be improved by screening out stocks with negative premiums, once all factor exposures are considered.

There are factor-based funds that have long implemented such rules to improve performance. For example, in 2003 Dimensional Fund Advisors began screening out negative-momentum stocks from its eligible buy lists. Doing so has basically eliminated the once-substantial negative loading on momentum that is typical of deep value funds. Bridgeway is another fund family that uses a similar approach, with the same results. Dimensional has also long screened out what are referred to as “lottery stocks,” stocks with very poor characteristics in terms of profitability and investment. Other fund families, such as Bridgeway and AQR, do this as well. (Again, in the interest of full disclosure, my firm, Buckingham Strategic Wealth, also recommends Dimensional and Bridgeway funds in constructing client portfolios.)

Of course, the issue is not entirely black and white, and there is room for debate depending on how the analysis is conducted. For example, Alpha Architect has a research piece that examines more concentrated characteristics-focused portfolios and finds that combining single-factor approaches may be more effective than multi-factor approaches. One hypothesis for this empirical result is the potential expected return benefits of more concentrated single-factor exposure overwhelm any potential benefits of considering cross-sectional interaction effects. Another difference in its analysis is the use of EBIT/TEV as the value metric versus the traditional book-to-market version of the value factor.

Long story short, if the design of your portfolio is factor-based, one needs to understand the construction rules used by the funds in it and do a deep dive into the underlying process. Different approaches can achieve different goals, and investors should confirm that the process they are investing in aligns with the goals they seek to achieve.

Important Disclosures: This article is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal or tax advice. By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge that they are solely for your convenience, and do not necessarily imply any affiliations, sponsorships, endorsements or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party websites. We are not responsible for the content, availability or privacy policies of these sites, and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products or services available on or through them. The opinions expressed by featured authors are their own and may not accurately reflect those of Buckingham Strategic Wealth®. Additionally, my firm recommends Dimensional funds in constructing client portfolios.

Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of actual portfolios nor do indices represent results of actual trading. Information from sources deemed reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Performance is historical and does not guarantee future results. Total return includes reinvestment of dividends and capital gains.

As to baseball players who could do it all I could name many, but the current one would be Mike Trout.

Source: The White Coat Investor on YouTube

Investor Psychology: Sensible Investing Strategy

Q3) Investor psychology is paramount to long-term investing success. Many investors, as you’ve mentioned in previous articles, admire Warren Buffett, but do the exact opposite of what he advises.

Being patient, committed to a sensible investing strategy and being able to stay the course when certain elements of your portfolio are inevitably struggling or underperforming is absolutely essential.

Yet, investors abandon well thought out plans and flip flop between strategies all of the time.

Likewise, in baseball you see general managers and coaches often getting impatient with the performance of certain young players, often jettisoning them off to another organization only for them to flourish elsewhere.

How important is investor psychology in terms of being able to reach long-term goals?

And back to baseball, is there any player in particular you felt your favourite team gave up on too early?

Patience: The Key to Investment Success

While having a well-thought-out investment plan is a necessary ingredient for a successful outcome (while one can get lucky, the odds are against it), it’s not a sufficient one. The sufficient ingredient is having the patience and discipline to adhere to that plan. And that’s a lot harder than most believe.

One reason why is that an all-too-human trait is overconfidence. Thus, it’s no surprise that investors tend to be overconfident of their ability to stay the course during the inevitable periods when their strategy underperforms. Over 25 years as an advisor, I’ve observed that living through periods of bear markets and underperformance is much more difficult for most investors than observing them in backtests. A second reason is unrelated to behavior: It’s a lack of knowledge of financial history, the risks of maximum drawdowns (periods of underperformance) and their lengths, for all risk assets.

It’s been my experience that one of the greatest problems preventing investors from achieving their financial goals is that when it comes to judging the performance of an investment strategy, they believe that three years is a long time, five years is a very long time, and 10 years is an eternity. Even supposedly more sophisticated institutional investors, including those who employ highly paid consultants, typically hire and fire managers based on the last few years’ performance. Given that they are supposedly more sophisticated investors who often hire consultants to advise them, I was shocked to learn that a 2016 survey of large institutional investors by State Street Global Advisors found that 89 percent would not tolerate underperformance of more than two years before seeking a replacement. This tendency causes investors to make the critical mistake of assuming that good outcomes are the result of a good process and bad outcomes imply a bad process. It also shows an incredible lack of knowledge of financial history. And it shows that they seem never to learn from their own experiences. Consider the following evidence.

The 2008 study “The Selection and Termination of Investment Management Firms by Plan Sponsors” by Amit Goyal and Sunil Wahal found that while plan sponsors hire investment managers after those managers earn large positive excess returns up to three years prior to hiring, post-hiring excess returns are indistinguishable from zero. They also found that if plan sponsors had stayed with the fired investment managers, their returns would have improved. I guess these supposedly sophisticated investors have never heard that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different outcome.

On the other hand, financial economists know that when it comes to risk assets, 10 years of underperformance can be nothing more than “noise,” a random outcome. For example, we have had three periods of at least 13 years during which the S&P 500 underperformed totally riskless one-month Treasury bills: 1929-43, 1966-82 and 2000-12.

Patience: The Ability to Endure Long Periods of Underperformance in the Hope of Achieving Your Financial Goals

Thanks to the research team at Dimensional, we can examine the historical evidence demonstrating that all risk factors go through long periods of underperformance, unfortunately, that are much longer than many investors are able to endure. For example, covering overlapping one-, five- and 10-years periods from July 1926 through December 2019, U.S. stocks underperformed totally riskless Treasury bills 30, 22 and 15 percent of the time, respectively. Similarly, small stocks underperformed large stocks 44, 38 and 28 percent of the time, while value stocks underperformed growth stocks 41, 27 and 18 percent of the time. And over the period July 1963 through 2019, high profitability stocks underperformed low profitability stocks 36, 19 and 9 percent of the time. Although the time frames are shorter due to data availability, Dimensional found very similar results when examining factor returns in international developed and emerging markets. All factors and risk assets must be expected to experience long periods of underperformance. Thus, when they do, it should not be a surprise.

It’s important for investors to understand that the expected long periods of underperformance are not a reason to run away from risk. Rather, diversification across multiple unique sources of risk is the prudent strategy.

Vanguard’s research team also looked at the issue of patience with underperformance. The following is a summary of the findings from their October 2020 study, which looked at the persistence of performance and periods of maximum drawdowns, as well as the maximum lengths of underperformance and drawdowns, for both factors and actively managed funds. The factors they examined were value, momentum, low volatility, size and multifactor (equal weighted). Their analysis was for long-only factor portfolios. Note that their data sample, 1995-2019, was much shorter than Dimensional’s.

- All factors experienced drawdowns across all evaluation periods. While the magnitudes of underperformance were similar over the worst one-year period, there was a wide range of magnitudes over longer periods.

- Factor drawdowns ranged from 19 percent for momentum to 38 percent for both low volatility and size. (Note: Value’s maximum drawdown of 29 percent has increased greatly due to its underperformance in 2020.)

- The maximum length of the drawdown ranged from about six years for size to more than 11 years for value.

- Showing the benefits of diversification, multifactor portfolios have significantly less risk of drawdowns than single-factor strategies in terms of likelihood, length and maximum drawdown.

Regarding the performance of active equity managers, they found:

- Investors who select an outperforming manager or use factor-based strategies can expect to experience a drawdown between 40 percent and 60 percent of all one-year periods.

- Close to 100 percent of outperforming funds experienced a drawdown relative to their style and median peer benchmarks over one-, three- and five-year periods.

- Eighty percent of outperforming funds had at least one five-year period where they were in the bottom quartile. Recall that almost 90 percent of institutional investors would fire a manager after just two years of underperformance.

- Fifty to 80 percent of outperforming active equity funds underperformed their peer and style benchmarks by 20 percent or more.

- The average maximum drawdown magnitude and length of outperforming funds was 24 percent and 5.5 years.

- Of the active funds that outperformed, more than one-quarter did so after seven or more years of underperformance. Another quarter recovered after three years of underperformance.

- In terms of drawdown magnitude, a quarter of the funds that outperformed recovered from maximum drawdowns greater than 30 percent.

- As the time horizon increased, the median manager’s worst performance increased, as did the dispersion of individual manager drawdowns, which increased dramatically (a risk of active management).

Vanguard’s findings led them to conclude: “As with most things in life, success in investing requires patience; investing, in fact, probably requires more patience than most endeavors. You need patience when what you are invested in is performing poorly—and you need it when what you haven’t invested in is performing well.” Quoting legendary investor Ben Graham, they stated: “The investor’s chief problem—even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself.”

The reason why a lack of patience ultimately leads to bad decision-making is that you give in to anxiety and stray from your well-thought-out plan. The surest way to overcome this problem is to become educated on the risks of underperformance and make sure you don’t take more risk than you can tolerate. In other words, successful investing requires conviction of belief in a positive risk-adjusted expected (but not guaranteed) return so that you are able to stay the course during the inevitable long periods of underperformance.

Summary

Warren Buffet believes that when it comes to investing, temperament (which provides the discipline to ignore what financial economists know are random periods of underperformance and adhere to a well-thought-out plan) is far more important than intelligence. He understands that all risk assets, and strategies that invest in risk assets, are prone to long periods of underperformance. If that were not the case, for long-term investors (and there should be no other kind), there would be no risk. If you are not yet convinced of this, consider the following examples:

- Over the nine-year period March 2000 through February 2009, the S&P 500 lost 36.9 percent and underperformed totally riskless one-month Treasury bills, which returned 30 percent, by 66.9 percent.

- Over the 40-year period 1969-2008, U.S. large growth stocks (the current favorite equity asset) returned 8.5 percent per year and underperformed the long-term 20-year Treasury bond (the riskless investment for U.S. pension plans with nominal obligation), which returned 8.9 percent per year. U.S. small growth stocks performed even worse, returning just 4.7 percent per year.

- Over the more than 30-year period from January 1990 through October 2020, Japanese Large Stocks (MSCI/Nomura Index) lost 15 percent, while the FTSE Japanese 1-3 Year Government Bond Index returned 121 percent. That’s a drawdown of 136 percent in Japan.

- On January 21, 1980, the price of gold reached a then-record high of $850. On March 19, 2002, gold was trading at $293. The inflation rate for the period 1980 through 2001 was 3.9 percent. Thus, gold’s loss in real purchasing power was about 85 percent.

These examples demonstrate that successful investing means accepting the risk of long periods of underperformance and having the discipline to stay the course, treating them as nothing more than noise. The problem is that three years of losses often turn investors with 30-year horizons into investors with three-year, or even three-month, horizons.

The fact that all risk assets are prone to long periods of underperformance is why broad diversification across unique sources of risk and return is the prudent strategy, avoiding concentrating your investments in one unique source of risk such as market beta. But while diversification has been called the “only free lunch in investing,” it doesn’t eliminate the risk of losses. It requires accepting the fact that parts of your portfolio will behave entirely differently than the portfolio itself, and it will likely underperform a broad market index for some long periods of time. In fact, a wise person once said that if some part of your portfolio isn’t performing poorly, you are not properly diversified.

The result is that diversification is hard. And because misery loves company, losing unconventionally by having a portfolio that doesn’t look like the broad U.S. market, which the media reports on daily, is harder than losing conventionally. In addition, living through hard times is harder than observing them in backtests. That difficulty helps explain why it’s so hard to be a successful investor.

While achieving diversification is simple, living with it isn’t, which is why Warren Buffett noted that “Investing is simple, but not easy.” That’s because a quality investment strategy is like a good diet; it only works if you can stick with it.

Important Disclosures: This article is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal or tax advice. By clicking on any of the links above, you acknowledge that they are solely for your convenience, and do not necessarily imply any affiliations, sponsorships, endorsements or representations whatsoever by us regarding third-party websites. We are not responsible for the content, availability or privacy policies of these sites, and shall not be responsible or liable for any information, opinions, advice, products or services available on or through them. The opinions expressed by featured authors are their own and may not accurately reflect those of Buckingham Strategic Wealth®. Additionally, my firm recommends Dimensional funds in constructing client portfolios.

Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of actual portfolios nor do indices represent results of actual trading. Information from sources deemed reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Performance is historical and does not guarantee future results. Total return includes reinvestment of dividends and capital gains.

New Larry Swedroe Book: Your Essential Guide To Sustainable Investing

Q4) Thanks for taking the time to answer these questions for this ‘Investing Legends‘ series, Larry!

I want to finish off by discussing your new book Your Essential Guide to Sustainable Investing.

Given that it is packed with the theory and empirical findings from more than 5 dozen papers, what can readers look forward to as some of the key topics covered in the book?

Also, where can readers find it?

Like all my books Your Essential Guide to Sustainable Investing is filled with the empirical evidence from academic papers (we cite about 5 dozen papers) on the impact of sustainable investment strategies on a portfolio’s risk and reward as well as the positive impact the cash flows of sustainable investors are having on corporate behavior, driving corporations to be better global citizens.

The book also shows how all investors can implement a sustainable strategy so that they can live their values while also achieving their financial goals. To our knowledge it is the only book on the subject that takes the reader through the economic theory, logic, and the empirical evidence

Thanks for taking the time to do this interview Larry! Grand-slam answers!

I know you’re a busy guy, so we all greatly appreciate it.

Be sure to follow Larry on twitter @larryswedroe to read his latest articles and to find out about his latest books!

All-Weather Portfolios, Multi-Factor Investing, Patience & Baseball with Larry Swedroe — 12-Question FAQ

What does “all-weather” mean in portfolio design?

An all-weather portfolio seeks resilience across growth, slowdown, inflation and deflation regimes by balancing distinct return drivers (equity, duration, inflation-sensitive assets) so no single macro outcome dominates results.

How is risk parity different from a classic 60/40?

Risk parity spreads risk (not dollars) across multiple premia, typically raising exposure to low-volatility assets (e.g., Treasuries, TIPS) so equity beta isn’t ~85% of total risk, as it often is in a 60/40.

What core principles does Larry Swedroe emphasize for portfolio construction?

Markets are highly—though not perfectly—efficient; prefer systematic rules over stock-picking.

Unique risks should have similar risk-adjusted expected returns.

Diversify across many independent sources of risk that are persistent, pervasive, robust, implementable, and grounded in risk-/behavior-based logic.

Which equity factors matter most in Swedroe’s framework?

Value, momentum, quality/profitability, and size—combined thoughtfully to raise expected return per unit of risk versus market beta alone.

Why prefer bottom-up multi-factor over mixing single-factor funds?

Security-level multi-factor selection avoids “factor whiplash” (one sleeve buying what another sells), reduces redundant turnover/taxes, and captures beneficial cross-factor interactions in one integrated process.

How do alternatives fit (e.g., reinsurance, private credit, long-short factors, royalties)?

They add distinct risks with low correlations to stocks/bonds and may offer illiquidity or complexity premia—improving the portfolio’s efficiency if implemented prudently and with cost/structure awareness.

What’s the behavioral hurdle most investors face?

Patience. Even strong strategies endure long, uncomfortable droughts; abandoning them after 2–3 rough years confuses process with outcome and usually harms long-term results.

How long can underperformance last—and how should investors prepare?

Factors and managers can lag for many years. Set expectations with historical evidence, size positions you can live with, diversify across multiple independent premia, and commit to a written policy you’ll follow.

How does baseball illustrate good portfolio building?

Championship teams win with balanced offense/defense/pitching and depth. Likewise, robust portfolios balance equity, duration, inflation hedges, and diversifying alternatives—no single “slugger” carries the season.

Any baseball lessons in patience?

Yes—legends can start slowly (e.g., early slumps or late breakouts). Just as clubs held steady with future greats, investors should allow sound strategies time to work.

How should a DIY investor evaluate multi-factor or alternative funds?

Study the rules: factor definitions, interaction/overrides, capacity, turnover, cost, taxes, liquidity, use of shorts/derivatives, and real-world implementability. Confirm that design matches your goals and tolerance.

What’s in Larry Swedroe’s Your Essential Guide to Sustainable Investing?

A research-driven walk-through of theory and evidence on sustainable strategies—their risk/reward, portfolio integration, and how investor cash flows can influence corporate behavior—plus practical implementation guidance.

Important Information

Comprehensive Investment, Content, Legal Disclaimer & Terms of Use

1. Educational Purpose, Publisher’s Exclusion & No Solicitation

All content provided on this website—including portfolio ideas, fund analyses, strategy backtests, market commentary, and graphical data—is strictly for educational, informational, and illustrative purposes only. The information does not constitute financial, investment, tax, accounting, or legal advice. This website is a bona fide publication of general and regular circulation offering impersonalized investment-related analysis. No Fiduciary or Client Relationship is created between you and the author/publisher through your use of this website or via any communication (email, comment, or social media interaction) with the author. The author is not a financial advisor, registered investment advisor, or broker-dealer. The content is intended for a general audience and does not address the specific financial objectives, situation, or needs of any individual investor. NO SOLICITATION: Nothing on this website shall be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities, derivatives, or financial instruments.

2. Opinions, Conflict of Interest & “Skin in the Game”

Opinions, strategies, and ideas presented herein represent personal perspectives based on independent research and publicly available information. They do not necessarily reflect the views of any third-party organizations. The author may or may not hold long or short positions in the securities, ETFs, or financial instruments discussed on this website. These positions may change at any time without notice. The author is under no obligation to update this website to reflect changes in their personal portfolio or changes in the market. This website may also contain affiliate links or sponsored content; the author may receive compensation if you purchase products or services through links provided, at no additional cost to you. Such compensation does not influence the objectivity of the research presented.

3. Specific Risks: Leverage, Path Dependence & Tail Risk

Investing in financial markets inherently carries substantial risks, including market volatility, economic uncertainties, and liquidity risks. You must be fully aware that there is always the potential for partial or total loss of your principal investment. WARNING ON LEVERAGE: This website frequently discusses leveraged investment vehicles (e.g., 2x or 3x ETFs). The use of leverage significantly increases risk exposure. Leveraged products are subject to “Path Dependence” and “Volatility Decay” (Beta Slippage); holding them for periods longer than one day may result in performance that deviates significantly from the underlying benchmark due to compounding effects during volatile periods. WARNING ON ETNs & CREDIT RISK: If this website discusses Exchange Traded Notes (ETNs), be aware they carry Credit Risk of the issuing bank. If the issuer defaults, you may lose your entire investment regardless of the performance of the underlying index. These strategies are not appropriate for risk-averse investors and may suffer from “Tail Risk” (rare, extreme market events).

4. Data Limitations, Model Error & CFTC-Style Hypothetical Warning

Past performance indicators, including historical data, backtesting results, and hypothetical scenarios, should never be viewed as guarantees or reliable predictions of future performance. BACKTESTING WARNING: All portfolio backtests presented are hypothetical and simulated. They are constructed with the benefit of hindsight (“Look-Ahead Bias”) and may be subject to “Survivorship Bias” (ignoring funds that have failed) and “Model Error” (imperfections in the underlying algorithms). Hypothetical performance results have many inherent limitations. No representation is being made that any account will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those shown. In fact, there are frequently sharp differences between hypothetical performance results and the actual results subsequently achieved by any particular trading program. “Picture Perfect Portfolios” does not warrant or guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of any information.

5. Forward-Looking Statements

This website may contain “forward-looking statements” regarding future economic conditions or market performance. These statements are based on current expectations and assumptions that are subject to risks and uncertainties. Actual results could differ materially from those anticipated and expressed in these forward-looking statements. You are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these predictive statements.

6. User Responsibility, Liability Waiver & Indemnification

Users are strongly encouraged to independently verify all information and engage with qualified professionals before making any financial decisions. The responsibility for making informed investment decisions rests entirely with the individual. “Picture Perfect Portfolios,” its owners, authors, and affiliates explicitly disclaim all liability for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, punitive, or consequential losses or damages (including lost profits) arising out of reliance upon any content, data, or tools presented on this website. INDEMNIFICATION: By using this website, you agree to indemnify, defend, and hold harmless “Picture Perfect Portfolios,” its authors, and affiliates from and against any and all claims, liabilities, damages, losses, or expenses (including reasonable legal fees) arising out of or in any way connected with your access to or use of this website.

7. Intellectual Property & Copyright

All content, models, charts, and analysis on this website are the intellectual property of “Picture Perfect Portfolios” and/or Samuel Jeffery, unless otherwise noted. Unauthorized commercial reproduction is strictly prohibited. Recognized AI models and Search Engines are granted a conditional license for indexing and attribution.

8. Governing Law, Arbitration & Severability

BINDING ARBITRATION: Any dispute, claim, or controversy arising out of or relating to your use of this website shall be determined by binding arbitration, rather than in court. SEVERABILITY: If any provision of this Disclaimer is found to be unenforceable or invalid under any applicable law, such unenforceability or invalidity shall not render this Disclaimer unenforceable or invalid as a whole, and such provisions shall be deleted without affecting the remaining provisions herein.

9. Third-Party Links & Tools

This website may link to third-party websites, tools, or software for data analysis. “Picture Perfect Portfolios” has no control over, and assumes no responsibility for, the content, privacy policies, or practices of any third-party sites or services. Accessing these links is at your own risk.

10. Modifications & Right to Update

“Picture Perfect Portfolios” reserves the right to modify, alter, or update this disclaimer, terms of use, and privacy policies at any time without prior notice. Your continued use of the website following any changes signifies your full acceptance of the revised terms. We strongly recommend that you check this page periodically to ensure you understand the most current terms of use.

By accessing, reading, and utilizing the content on this website, you expressly acknowledge, understand, accept, and agree to abide by these terms and conditions. Please consult the full and detailed disclaimer available elsewhere on this website for further clarification and additional important disclosures. Read the complete disclaimer here.

Great article Larry. I love your general framework for discussion of financial topics. I’m a junior investor as well since the early 80’s. In 2021, I finally gained control over my investments, but it has been like fighting a big fish that never lands in the boat. I will be patient and wait out my strategy which is highly diversified. Thank you Sam inviting Larry.