Corporate finance is an ever-evolving world. Once upon a time, companies that had “excess” capital would distribute it to shareholders in the form of dividends, often paid quarterly, year in and year out. For decades, this was the norm, a sign of corporate stability and goodwill toward shareholders. But times changed. Buybacks arrived.

Share buybacks—also known as repurchases—are programs where a company purchases its own outstanding shares from the open market or directly from shareholders. This reduces the total share count, potentially boosting metrics like earnings per share (EPS). Over the last two decades, stock buybacks have become a mainstay for many publicly traded companies. They’ve arguably become as important as dividends for returning cash to shareholders.

But not all buybacks are created equal. Enter buy-back accelerators, a unique approach that speeds up the process, often referred to as Accelerated Share Repurchase (ASR) programs. Instead of buying a small portion of shares each quarter or intermittently throughout the year, a company can partner with an investment bank to repurchase a large block of shares immediately. The bank effectively short-sells the company’s stock, then gradually repurchases those shares in the open market to close out its position over an agreed-upon time frame. The result? The company slashes its share count in one swift move, sending a strong and immediate signal to the market that says, “We’re confident, and we’re putting our money where our mouth is.”

Why Buck-Back Accelerators?

Why do this? The reasons vary. Some companies want to signal financial strength or undervaluation. Others have large cash hoards and few attractive growth opportunities on the horizon. Still others see buybacks as a tax-efficient means of returning capital, especially in certain jurisdictions where dividends face heavier tax burdens. Whatever the impetus, buy-back accelerators have become a powerful lever for companies with the financial muscle—and the appetite for big, bold moves.

But caution is crucial.

An accelerated share repurchase can backfire if the stock is overpriced, if the company piles on debt, or if external factors upset the careful balancing act of the ASR transaction. Critics argue that buybacks, especially accelerated ones, can be short-term oriented, benefiting executives whose compensation is tied to EPS metrics. Meanwhile, these critics claim, the broader economy loses out if companies forgo reinvestment in research, employee wages, or other long-term initiatives. Regulators and policymakers have noticed. Debate rages on.

We’ll explore every aspect of these buy-back accelerators—what they are, how they work, why companies use them, and what it all means for investors. We’ll also examine real-world examples of major corporate players who’ve used ASRs to reshape their capital structure. By the end, you should have a nuanced grasp of this potent tool, equipped to interpret headlines about “record-breaking share repurchases” with a more critical eye.

Let’s start by clarifying precisely what buy-back accelerators are, and how they differ from the simpler, more familiar forms of share repurchase programs.

What Are Buy-Back Accelerators?

A buy-back accelerator, most commonly referred to as an Accelerated Share Repurchase (ASR), is an agreement between a company and an investment bank—or a consortium of banks—to repurchase a large number of the company’s shares immediately. This approach condenses what might have been months or years of gradual share buybacks into a single moment, giving the company instant gratification in terms of reduced share count and, by extension, a swift EPS enhancement.

It’s a bold move.

How an ASR Typically Works

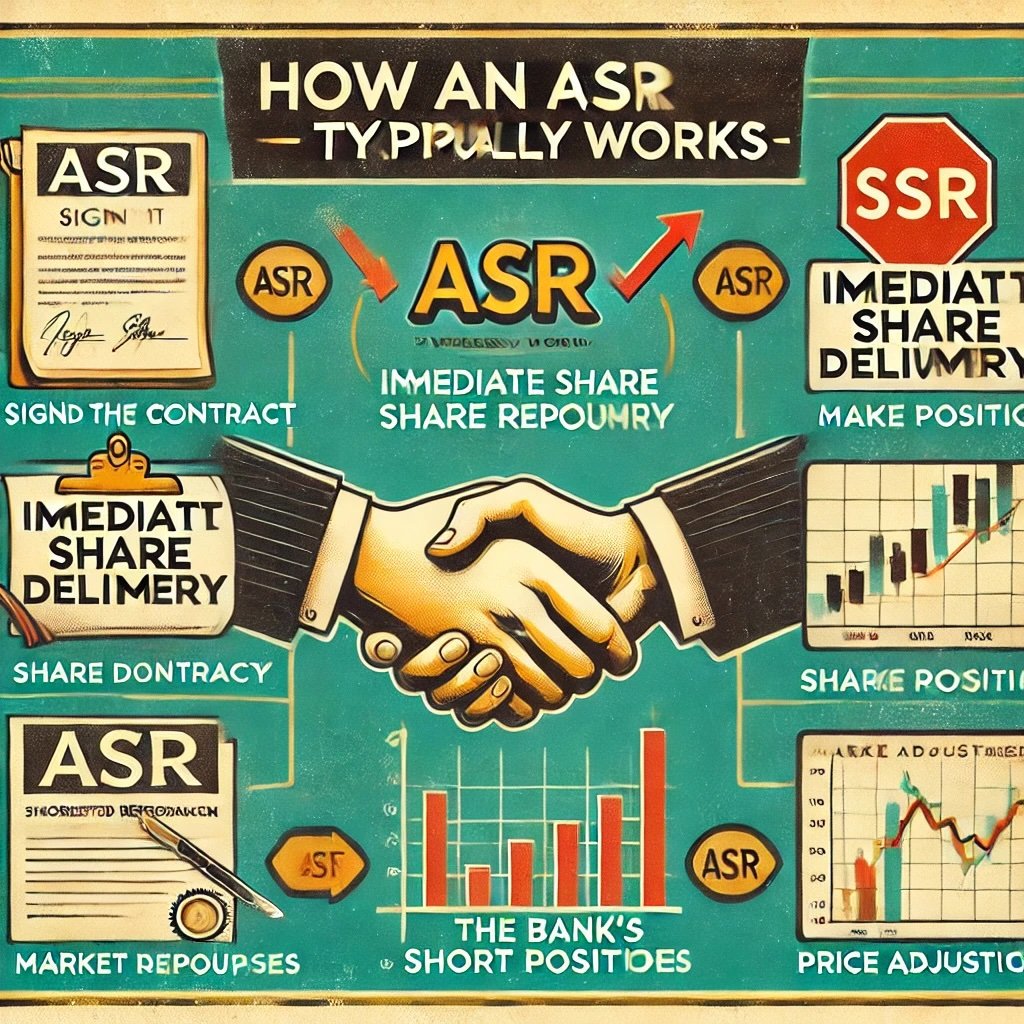

- Signing the Contract

The company (let’s call it “XYZ Corp”) signs an agreement with an investment bank. XYZ Corp pays the bank a lump sum of cash upfront, based on a rough estimate of how many shares will be purchased. - Immediate Share Delivery

The bank delivers a majority (often 80–90% or more) of the agreed-upon shares to XYZ Corp straight away. This means XYZ Corp’s share count drops, and they can announce, “We’ve just bought back X million shares,” which can have a significant psychological and market impact. - Bank’s Short Position

Since the bank might not currently own enough of XYZ Corp’s shares to deliver them all at once, it creates a short position. It effectively borrows shares or uses other mechanisms to deliver them to the company upfront. - Market Repurchase Over Time

In the background, the bank will buy back the shares (in the open market) that it needs to close out its short position. This can take several weeks or months. The final price the bank pays—and thus the final cost to the company—will be determined by how the stock trades during this period. - Price Adjustment

Sometimes, there’s a “true-up” or price adjustment at the end of the ASR period. If the stock’s average price is lower than initially estimated, the bank might deliver additional shares to the company. If the stock’s average price is higher, the company might have to pay extra. Various contractual provisions can influence these dynamics.

Why Companies Choose ASRs Over Traditional Buybacks

- Speed and Impact: Traditional buybacks can be incremental—maybe the company repurchases a set value each quarter. An ASR compresses that timeline, making the effect on share count felt immediately.

- Signaling Undervaluation: A bold, upfront repurchase suggests management strongly believes the stock is undervalued. Investors can perceive this as a vote of confidence, potentially boosting the share price.

- Efficient Use of Cash: If a company decides it no longer needs the cash for mergers, acquisitions, or expansions, an ASR can be a quick method to reduce “idle” capital.

- Reduced Market Impact: By offloading the repurchase activity to the bank, the company itself avoids months of open-market activity that can drive up its own share price. The bank’s trading is more discreet over time.

Contrasting ASRs with Traditional Buybacks

- Traditional Buyback: The company announces a plan to buy back a certain dollar amount (or share count) of its stock over a specified period—often months or years. The repurchases happen slowly, often at management’s discretion, or by following a pre-set schedule.

- Accelerated Share Repurchase: The bulk of the shares are effectively repurchased right away. The final settlement is determined over the following weeks or months, but from an accounting and EPS perspective, the share count is slashed almost immediately.

ASRs are more aggressive.

In some cases, companies use a mix of both methods—an upfront ASR for maximum headline impact and ongoing open-market buybacks afterward to fine-tune their capital structure. Regardless of the approach, share repurchases, and specifically accelerated programs, are a hallmark of a company that believes in its financial health or wants to return capital to shareholders in a tax-efficient manner.

But as with any financial innovation, buy-back accelerators come with pros and cons. Let’s move on to the benefits that drive corporate leaders to implement these strategies in the first place.

Benefits of Buy-Back Accelerators

Companies often tout their share repurchase programs as evidence that they stand behind their own stock. By removing shares from circulation, these companies aim to improve various financial metrics and send a clear signal about their bullish outlook. ASRs magnify these advantages, delivering them more swiftly than traditional buybacks. In this section, we’ll explore the core benefits that make buy-back accelerators so appealing to many corporate boards and executive teams.

1. Boost to Earnings Per Share (EPS)

Earnings per share is a widely watched metric. It directly influences valuations, especially for companies in sectors where EPS is a key performance indicator. By reducing the denominator (the number of shares outstanding), a company can increase its EPS without actually growing net income. This can look attractive on quarterly earnings calls or in annual reports.

Higher EPS can lift share prices.

Moreover, ASRs accelerate this effect. Instead of waiting months for incremental buybacks to reflect on financial statements, the company can see an immediate jump in EPS, potentially pleasing investors and analysts alike.

2. Strong Market Signal

Corporate finance is part economics, part psychology. A bold, accelerated share repurchase says: “We have so much confidence in our future that we’re committing a large sum right now.” This can embolden investors who may have been on the fence. It can also deter short-sellers who see the company’s stock as overvalued, because the firm is effectively betting on its own undervaluation.

Additionally, the immediate share reduction can catch market participants’ attention, often sparking coverage in financial media. Executives sometimes use this to shift the narrative, especially if the company’s recent press has been negative or if the firm has faced criticism about capital allocation.

3. Quick Deployment of Excess Cash

While holding ample cash can be a safety net, too much idle cash can weigh down a company’s return on equity. Investors sometimes pressure management to either:

- Reinvest in growth (acquisitions, R&D, or expansion).

- Pay higher dividends.

- Initiate share buybacks.

For companies that lack attractive growth opportunities, an accelerated buyback is a swift solution: the surplus cash disappears from the balance sheet, but it bolsters certain per-share metrics. This can be more appealing to management than raising dividends, which create an ongoing payout obligation. A buyback is generally considered a one-time or periodic event, giving companies more flexibility if market conditions shift later.

4. Shareholder Value Creation

From a shareholder’s perspective, ASRs can lead to a tangible increase in the value of remaining shares—assuming the market re-rates the stock upward due to the decreased supply or improved metrics. Additionally, many argue that if a company believes its stock is undervalued, repurchasing shares is an intelligent capital allocation method: the firm is essentially investing in itself at a “discount.”

5. Tax Efficiency

In certain jurisdictions, share buybacks can be more tax-friendly than dividends for shareholders. Dividends are typically taxed as income (though the exact rate varies by country and type of investor), whereas an increased share price from buybacks isn’t taxed until the shareholder sells the shares. Even then, it might be subject to capital gains tax rates, which can be different (and sometimes lower) than dividend tax rates. Although legislation and tax codes are continually shifting, many U.S. corporations have historically viewed buybacks as a tax-efficient way to return capital to shareholders.

Fewer taxes mean happier investors.

Balancing Short- vs. Long-Term Benefits

While all these benefits are compelling, critics argue that companies can become too fixated on short-term metrics like EPS, sometimes neglecting longer-term investments that might yield greater future returns. We’ll delve deeper into these counterarguments in the Risks and Considerations section. Nonetheless, from the corporate perspective, when executed at the right time and with the right intentions, an ASR can significantly enhance shareholder value and strengthen investor confidence.

Risks and Considerations

While buy-back accelerators offer an array of potential upsides, they are not without pitfalls. Financial maneuvers of this nature can misfire, especially if market conditions change unexpectedly or if the company’s leadership fails to exercise prudent judgment about its share price and capital structure. Let’s examine the key risks and considerations that investors, executives, and stakeholders must keep in mind when an ASR is on the table.

1. Overvaluation Risk

One of the primary objectives of a buyback is for a company to take advantage of what it perceives as an undervalued share price. But what if management is mistaken, or overly optimistic? If a company’s shares are actually trading at or above their fair value, a large buyback could essentially waste capital. The firm could end up paying a premium for its own shares, only to see the stock decline later.

This can be costly.

Moreover, an ASR can amplify this miscalculation by committing a large sum upfront. In a traditional buyback, at least the company might gradually buy shares, adjusting to market fluctuations along the way. But with an ASR, the cost is largely “locked in.” Final settlements might account for price changes, but the initial commitment can be huge.

2. Debt Financing Concerns

If a company is flush with cash, financing an ASR might be straightforward. But if it’s not, the firm may opt to issue debt or tap credit lines to repurchase shares. This increases leverage and can elevate financial risk. Shareholders might enjoy a short-term EPS boost, but the long-term consequences of higher interest payments and decreased financial flexibility could overshadow any near-term gains.

Critics often point to situations where corporate debt skyrockets while management aggressively buys back shares, suggesting that the practice prioritizes short-term price support over balance-sheet strength. If an economic downturn hits, that debt can become a major liability.

3. Short-Term Focus

Buybacks, in general, can be accused of feeding short-term thinking among executives. Because EPS is a crucial factor in equity valuation—and often in determining executive bonuses—a company might be tempted to direct cash toward share repurchases rather than long-term investments. While this can momentarily please analysts and certain shareholders, it may undermine corporate innovation, expansion, or workforce development in the future.

ASRs magnify this tension because they’re immediate and large-scale. It’s one thing to buy back shares steadily as free cash flow accumulates. It’s another to pour billions into a rapid repurchase, potentially leaving the company less able to pursue new projects or acquisitions down the line.

4. Market Volatility

Accelerated Share Repurchases often include a settlement period of weeks or months, during which the investment bank is purchasing shares to close its short position. If the stock price swings wildly, the final accounting can differ significantly from initial estimates. This can result in:

- Additional shares delivered to the company if the price is lower than expected.

- Additional payments required from the company if the price is higher.

- Overall unpredictability in how many shares are ultimately retired and at what net cost.

5. Regulatory and Perception Risks

In recent years, legislators and the public have grown more critical of buybacks, especially when they occur at times when the company is also laying off workers or paying minimal taxes. Some argue that share repurchases can inflate stock prices, benefiting insiders who sell at peak prices rather than truly investing in the firm’s future. As such, a high-profile ASR can draw scrutiny, leading to negative press or calls for legal or regulatory reform.

Furthermore, certain jurisdictions may impose taxes or constraints on buybacks. If political winds shift, companies that rely heavily on ASRs could find themselves in a more restrictive environment. At the very least, they risk a public relations backlash if their buyback programs are perceived as undermining broader social or economic priorities.

6. Opportunity Cost

Money spent on an ASR is money not spent on potential acquisitions, research and development, expanding into new markets, or paying down debt. The latter might be especially pertinent if interest rates are rising. Executives must weigh whether the immediate share reduction is truly the best use of capital. If a technology revolution or market disruption arises and the company lacks the financial resources to respond, shareholders might regret the repurchase spree.

Be careful choosing priorities.

Examples of Companies Using Buy-Back Accelerators

Buy-back accelerators aren’t just theoretical constructs on a whiteboard in some finance department. They’re widely used by some of the biggest names in the corporate world. In this section, we’ll explore notable companies that have employed ASRs, delving briefly into the rationale behind their decisions and the outcomes—both positive and negative.

Apple

Over the last decade, Apple has been synonymous with massive stock buybacks. In fact, Apple’s repurchase programs have often ranked as some of the largest in history. While Apple employs both traditional buybacks and accelerated ones, the ASR component of its strategy has been significant at times. Why?

- Excess Cash: Apple famously hoarded cash. With limited immediate acquisitions in sight, it used repurchases to return capital to shareholders.

- Confidence Signal: Apple’s leadership has consistently stated it believes the market undervalued the company’s ecosystem, brand loyalty, and services growth prospects.

- EPS Focus: Reducing share count helped Apple maintain an upward trend in EPS, bolstering investor confidence and share price momentum.

Outcome: Apple’s buyback spree generally aligned with strong fundamental performance. Critics might point to missed opportunities for massive M&A or deeper R&D, but shareholders have often been pleased with the total returns.

Alphabet (Google)

Alphabet—parent of Google—has also executed share repurchases, sometimes in accelerated form, to consolidate ownership and reduce dilution from employee stock compensation. Alphabet’s repurchases serve a dual purpose:

- Stock Compensation Offset: Google pays a substantial amount of compensation via stock options or restricted stock units. Buybacks can offset the dilutive effect on share count.

- Confidence: Alphabet’s core businesses (search, YouTube, cloud) generate strong free cash flow, so management sees buybacks as a logical use of funds.

- Moderate Shareholder Returns: While Alphabet doesn’t pay dividends, these repurchases can be viewed as a partial return of capital to shareholders.

Outcome: Alphabet remains flush with cash, so the net effect of these buybacks has been somewhat neutral on the balance sheet. However, they do support the share price, and many market observers see them as an affirmation that Alphabet’s management believes in long-term growth.

ExxonMobil

When oil prices spike, ExxonMobil often finds itself awash in profits. Historically, it has used some of this windfall to reward shareholders through dividends and buybacks. ASRs can be an efficient way for ExxonMobil to manage its capital structure, especially if management believes the stock is undervalued relative to the company’s vast energy reserves.

- Strategic Timings: Often aligned with times when oil prices are high, providing ample free cash flow.

- Criticisms: Some environmental or activist shareholders argue that ExxonMobil should direct more capital toward transitioning to renewables rather than buying back stock.

- Volatility: The share price can swing with commodity prices, making buybacks a timing gamble.

Outcome: ExxonMobil’s buybacks, including any accelerated programs, generally boost EPS in the short term but can raise questions about whether more capital should be allocated toward long-term energy transitions.

Meta Platforms (Facebook)

Meta Platforms, previously Facebook, has relied on buybacks to bolster market confidence, especially after facing tough scrutiny over privacy issues and competition. When its share price sagged (for instance, after user growth concerns or regulatory crackdowns), Meta occasionally leveraged buybacks to:

- Communicate Undervaluation: Signaling that despite controversy or slowed growth, the company sees its own stock as worth more than the market currently prices it.

- Sustain Share Price: In the tech sector, maintaining a strong share price helps with employee morale, stock-based compensation, and broader brand perception.

- Adapt to Changing Trends: With a pivot to the Metaverse, buybacks can reassure investors that the core advertising business remains robust enough to fund both expansions and share repurchases.

Outcome: The results have been mixed. While buybacks offered short-term EPS enhancements, some critics felt that capital could have been spent on either acquisitions or in developing technologies to keep pace with rivals. Still, many shareholders welcomed the immediate returns.

Case Studies and Outcomes

- Successful: Apple’s repeated buyback programs have often coincided with robust earnings growth, solidifying shareholder belief that the capital was well-used.

- Controversial: Meta’s buybacks in certain periods have raised eyebrows, especially when the company faced strategic headwinds or was in the midst of pivoting to new platforms.

- Industry-Specific: In cyclical sectors like oil, timing is everything. ExxonMobil’s buybacks can be highly beneficial when done at opportune moments but can look questionable if commodity prices collapse soon after.

These examples illustrate that while an ASR can be a powerful statement, outcomes vary depending on market conditions, the company’s broader strategy, and the timing of the repurchase. Investors analyzing such moves should consider the firm’s motivation, the sector’s volatility, and whether the repurchased shares genuinely were undervalued.

Buy-Back Accelerators (ASRs): 12-Question FAQ

1) What is a buy-back accelerator (ASR)?

An Accelerated Share Repurchase (ASR) is a contract where a company prepays a bank to retire a large block of shares immediately; the bank delivers most shares up front and later buys stock in the market to close its short, with a final “true-up” based on the average price during the program.

2) How is an ASR different from a regular buyback?

Traditional buybacks dribble purchases over months/years; an ASR compresses the effect into day one (outstanding shares fall fast; EPS lifts sooner), with a post-period settlement that adjusts the final share count or cash.

3) Why do companies use ASRs?

Speed and signaling (confidence/undervaluation), EPS uplift timing, balance-sheet optimization (deploying excess cash), discretion (bank handles trading), and dilution offset (employee stock comp) are the main motives.

4) What are the headline benefits for shareholders?

Immediate per-share math (EPS, free cash flow/share), potentially higher price support from reduced float, tax efficiency vs dividends for some investors, and clarity of commitment (large, disclosed dollar amounts).

5) What are the key risks?

Overpaying if shares are expensive, higher leverage if funded with debt, short-termism (EPS optics over reinvestment), settlement surprises if volatility spikes, and potential regulatory/PR scrutiny.

6) How does the “true-up” work?

At the end of the measuring window, if the stock’s volume-weighted average price (VWAP) is below the initial reference, the company typically receives more shares; if above, it may owe cash or receive fewer shares—per contract terms.

7) What accounting/metric effects show up first?

Weighted-average diluted shares: drop immediately (partial), improving EPS.

Equity & cash: cash down at inception; treasury stock up.

Leverage ratios: may rise if debt finances the ASR.

Per-share metrics (EPS/FCF/share/ROE): often improve mechanically.

8) How should investors judge ASR quality?

Look for: (a) valuation discipline (repurchases near/below intrinsic value), (b) balance-sheet prudence (net leverage, interest coverage), (c) durable free cash flow after capex, (d) clear capital-allocation framework (buybacks vs growth vs debt paydown), and (e) measured program size (<~1–1.5× annual FCF is a common sanity check).

9) What red flags should I watch?

Debt-funded ASRs when end-markets weaken, repurchases while operating margins/comps slide, “mega” ASRs that exceed realistic FCF, heavy SBC that offsets repurchases, and shifting guidance that leans on EPS optics over operating progress.

10) How do ASRs interact with stock-based compensation?

ASRs can neutralize dilution from SBC. Track gross repurchase dollars minus SBC value issued; if the net share count isn’t falling meaningfully year over year, the buyback is just treading water.

11) What’s a practical investor checklist?

Entry valuation (P/E vs normalized earnings, FCF yield)

Net debt/EBITDA before & pro forma

Interest expense sensitivity to rates

Percent of float retired and pace (days’ volume)

Net share count change over 1–3 years

Capital returns mix (dividends vs buybacks) vs reinvestment needs

12) Who benefits most from ASRs?

Long-term holders when buybacks occur at attractive valuations with conservative funding; management teams that align incentives with value creation per share (not just EPS), and firms with durable, high-visibility FCF.

Conclusion

Stock buybacks have become a mainstay in corporate America, rivaling (and sometimes eclipsing) dividends as the preferred method for returning capital to shareholders. Buy-back accelerators, or Accelerated Share Repurchases (ASRs), take this idea to a new level of intensity, allowing companies to rapidly reduce their share count and amplify the beneficial optics. By partnering with an investment bank, these firms can effectively lock in a share reduction in a matter of days rather than months or years, sending a bold message to the market that they believe in their own future prospects.

But the stakes are high.

Key Takeaways

- Mechanics: An ASR involves an upfront payment to an investment bank, which delivers most of the shares immediately. The bank then gradually buys those shares on the open market to settle its short position, while a final “true-up” adjusts for any price differentials.

- Benefits:

- Instant EPS Boost

- Strong Market Signal

- Efficient Use of Excess Cash

- Tax-Friendly Compared to Dividends

- Risks:

- Overvaluation: Buying back shares at inflated prices wastes capital.

- Debt Financing: Funding buybacks with debt can strain balance sheets.

- Short-Term Focus: Raises concerns about neglecting long-term investments.

- Market Volatility: The final cost can vary if share prices fluctuate significantly during the settlement period.

- Reputational: Regulatory scrutiny and public perception can turn negative if repurchases seem to prioritize shareholder returns over other corporate or societal needs.

- Real-World Examples: Giants like Apple, Alphabet, ExxonMobil, and Meta have all used ASRs to various degrees. Their outcomes highlight that while these moves can please Wall Street in the short run, they can also spark debates about capital allocation and corporate priorities.

Putting It All Together

Buy-back accelerators exist at the intersection of capital management, investor relations, and corporate strategy. When used judiciously—especially if the stock is truly undervalued—they can deliver a meaningful jolt to EPS and bolster the confidence of shareholders and analysts. Yet, caution must be exercised. If the company overestimates its value, or if it borrows heavily just to repurchase shares, that can create complications down the road. Furthermore, in a world increasingly concerned with corporate responsibility, some critics argue that ballooning buyback programs do little to serve broader societal or economic needs. They ask: Shouldn’t that capital be funneled into employee wages, climate initiatives, or long-term research and development?

The truth, as often is the case, lies somewhere in the middle. ASRs can be powerful tools when companies see no better uses for their cash and genuinely believe the stock is trading below intrinsic value. But they’re not a panacea. Investors should remain vigilant, examining not just the buyback itself but the context: Is the company strong in its fundamentals, or is it using buybacks as a quick fix to impress the market? Is the share repurchase part of a broader capital strategy that includes prudent investment in growth areas, or is it effectively a short-term patch?

Context is everything.

Why and When to Pay Attention

If you see a major ASR announcement, ask yourself:

- Is the company’s financial footing strong, or does it carry significant debt?

- What does management say about the stock’s valuation?

- Is the company simultaneously trimming crucial budgets or workforce investments?

- How have past buyback programs fared? Did the stock price appreciate afterward, or did it falter?

- Are there looming regulatory changes that might affect the tax treatment or perception of buybacks?

Answering these questions can offer clarity on whether the buyback is likely to yield lasting shareholder value or merely act as a short-lived attempt to lift quarterly figures.

Final Thoughts

Buy-back accelerators spotlight the dynamism and complexity of corporate finance. In an age where many CEOs face pressure from activist investors, social stakeholders, and short-term market metrics, it’s no surprise that ASRs have gained momentum. They allow for quick, headline-grabbing share count reductions and can appease certain sections of Wall Street. But they also come with heightened risk and moral scrutiny.

For investors, knowledge is power. The more you understand about how ASRs function—and about the nuanced interplay of capital allocation, market sentiment, and regulatory context—the better positioned you are to gauge whether these “races to reduce share count” truly serve the company’s long-term health, or whether they’re simply fueling another market mania. At the end of the day, buy-back accelerators can be a potent testament to a company’s confidence or a harbinger of misplaced priorities. The differentiating factor often lies in thoughtful execution, transparent communication, and alignment with a coherent corporate vision.

Important Information

Comprehensive Investment Disclaimer:

All content provided on this website (including but not limited to portfolio ideas, fund analyses, investment strategies, commentary on market conditions, and discussions regarding leverage) is strictly for educational, informational, and illustrative purposes only. The information does not constitute financial, investment, tax, accounting, or legal advice. Opinions, strategies, and ideas presented herein represent personal perspectives, are based on independent research and publicly available information, and do not necessarily reflect the views or official positions of any third-party organizations, institutions, or affiliates.

Investing in financial markets inherently carries substantial risks, including but not limited to market volatility, economic uncertainties, geopolitical developments, and liquidity risks. You must be fully aware that there is always the potential for partial or total loss of your principal investment. Additionally, the use of leverage or leveraged financial products significantly increases risk exposure by amplifying both potential gains and potential losses, and thus is not appropriate or advisable for all investors. Using leverage may result in losing more than your initial invested capital, incurring margin calls, experiencing substantial interest costs, or suffering severe financial distress.

Past performance indicators, including historical data, backtesting results, and hypothetical scenarios, should never be viewed as guarantees or reliable predictions of future performance. Any examples provided are purely hypothetical and intended only for illustration purposes. Performance benchmarks, such as market indexes mentioned on this site, are theoretical and are not directly investable. While diligent efforts are made to provide accurate and current information, “Picture Perfect Portfolios” does not warrant, represent, or guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of any information provided. Errors, inaccuracies, or outdated information may exist.

Users of this website are strongly encouraged to independently verify all information, conduct comprehensive research and due diligence, and engage with qualified financial, investment, tax, or legal professionals before making any investment or financial decisions. The responsibility for making informed investment decisions rests entirely with the individual. “Picture Perfect Portfolios” explicitly disclaims all liability for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, consequential, or other losses or damages incurred, financial or otherwise, arising out of reliance upon, or use of, any content or information presented on this website.

By accessing, reading, and utilizing the content on this website, you expressly acknowledge, understand, accept, and agree to abide by these terms and conditions. Please consult the full and detailed disclaimer available elsewhere on this website for further clarification and additional important disclosures. Read the complete disclaimer here.