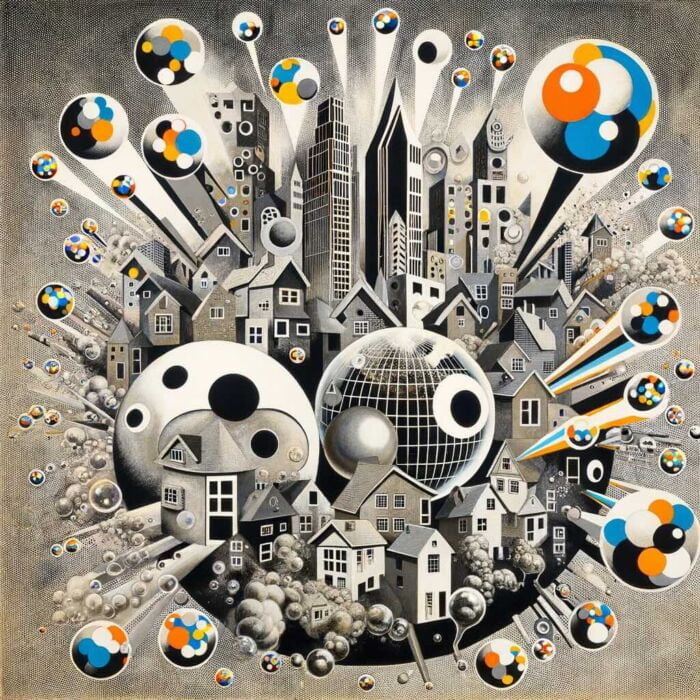

A housing bubble occurs when the prices of homes rise at an unprecedented and unsustainable rate, often driven by speculation, demand, and the belief that the upward trajectory will continue indefinitely. This is not just a mere increase in property values. It’s a rapid inflation that stretches beyond the ordinary market dynamics of supply and demand. At the heart of a bubble lies a mixture of irrational exuberance, unfettered optimism, and the treacherous illusion of perpetual growth.

What is a Housing Bubble?

Historically, housing bubbles have been characterized by an initial spark—be it easy access to mortgage credit, low-interest rates, or another external stimulus—which ignites rapid home buying. As demand escalates, so does supply, leading builders to construct homes at a frenzied pace. The increasing home prices lure more investors into the market, often hoping to “flip” homes for a quick profit. As prices surge further, fear of missing out spurs even more people to buy, adding fuel to the fire.

Yet, like all bubbles, there’s a point when they burst. The very factors that drove prices up—easy credit, speculation, overbuilding—become liabilities. Homeowners find themselves “underwater”, owing more on their mortgages than their homes are worth. This, coupled with a decline in demand and an oversupply of homes, causes prices to plummet, leading to foreclosures, economic downturns, and, in worst cases, financial crises.

Why Study Past Housing Bubbles?

Understanding the past provides us with a valuable tool to predict, if not prevent, similar occurrences in the future. Each housing bubble, though unique in its origins and outcomes, offers lessons about the broader economic, psychological, and regulatory factors at play.

The financial implications of a housing bubble are vast and varied, affecting not just homeowners and investors but entire economies. From Tokyo in the 1980s to the U.S. in 2007-2008, the ripple effects of a housing bubble crash have led to recessions, bank collapses, and countless personal tragedies.

But beyond the financial repercussions, housing bubbles also have significant societal implications. Homes are more than just assets; they’re where we build our lives, raise families, and create memories. When bubbles burst, they don’t just disrupt markets—they disrupt lives.

Thus, studying these events isn’t just an academic exercise. It’s an urgent imperative, a means to protect our economies and societies from the devastating aftermath of irrational exuberance gone awry. By analyzing the mistakes and oversights of the past, we can hope to chart a more stable and sustainable course for the future of housing markets worldwide.

source: Joe Manausa Real Estate on YouTube

The Anatomy of a Housing Bubble

The Life Cycle of a Bubble

Much like living organisms, housing bubbles go through distinct stages in their life cycle. Recognizing these stages is crucial for policymakers, investors, and the general public to understand, respond to, and potentially mitigate the impacts of a bubble. The four fundamental stages of a housing bubble are: Takeoff, Boom, Froth, and Burst.

1. Takeoff

The seeds of a housing bubble are sown during the Takeoff phase. Here, the market begins to recover from a period of stagnation or decline. Several factors can trigger this recovery:

- Economic Growth: A robust economy can increase the purchasing power of consumers, leading to a surge in demand for homes.

- Low-Interest Rates: Central banks might decrease interest rates to spur economic growth, making borrowing cheaper. Consequently, mortgages become more affordable, fueling a spike in home buying.

- Innovation in Financing: New financial instruments or relaxed lending criteria can enable more people to buy homes, even those who may not be financially secure.

While these factors are often well-intentioned, they can inadvertently lay the groundwork for a bubble. During the takeoff stage, increased demand starts to outstrip supply, and prices begin their upward climb.

2. Boom

In the Boom phase, the upward trajectory of home prices gains momentum. Several dynamics play out during this phase:

- Positive Feedback Loop: As prices rise, more and more people believe that they will continue to do so. This belief drives further buying, pushing prices up even more.

- Speculative Investing: Seeing the potential for high returns, investors enter the market, often buying properties with the intention of selling them quickly for a profit. This speculative buying accelerates the rate of price increase.

- Media Hype: The media starts to focus on the “booming” housing market, with stories of people making significant profits in real estate. This coverage often lacks a critical perspective, further fueling the belief that this growth is sustainable.

The boom phase is characterized by widespread optimism. The general sentiment is that investing in real estate is a “sure thing.

3. Froth

The Froth stage is the tipping point. Here, the signs of an overheated market become more evident, but they’re often rationalized or outright ignored. Key indicators include:

- Skyrocketing Prices: Home prices reach unsustainable levels, often detached from fundamental economic indicators like wage growth or rental income.

- Over-leveraging: Encouraged by the boom, many consumers take on significant debt, believing that their assets will continue to appreciate and cover their liabilities.

- Supply Outpacing Demand: Construction projects, started during the boom phase, come to completion. The market starts to have an oversupply of properties, but the demand starts to wane, especially from genuine homebuyers.

During the froth phase, doubts creep in, but the prevailing belief remains that the market will correct itself without a significant downturn.

4. Burst

The Burst phase is the painful end of the bubble. The factors that propped up the market reverse:

- Trigger Event: An external event, such as an interest rate hike, economic recession, or another shock, makes it difficult for homeowners to service their debts.

- Mass Selling: Homeowners and investors try to offload properties. With the oversupply from the froth stage, prices plummet rapidly.

- Foreclosures: Many homeowners, especially those who over-leveraged during the froth phase, find themselves unable to meet mortgage payments. This leads to a spike in foreclosures, further flooding the market with properties and driving prices even lower.

The burst phase is characterized by rapid decline, panic, and significant financial loss. It’s a stark reminder of the dangers of unchecked optimism and speculative investing.

Understanding the anatomy of a housing bubble provides us with tools to recognize early warning signs and, hopefully, implement measures to prevent or mitigate the effects of a burst. While each housing bubble has unique features based on regional and temporal contexts, these stages are consistent across different scenarios. Recognizing them is the first step towards ensuring a stable and sustainable housing market.

Lesson 1: External Stimuli Often Play a Role

Housing bubbles rarely arise in isolation. They’re often catalyzed, and at times exacerbated, by a blend of external factors. Recognizing the significant role these stimuli play can be pivotal for policymakers and market participants alike, enabling them to anticipate potential hazards and navigate through tumultuous economic waters.

U.S. Low-Interest Rates Leading Up to the 2008 Crash: A Case Study

In the early 2000s, the U.S. Federal Reserve, in a bid to stimulate the economy after the dot-com bust and the fallout from the 9/11 attacks, slashed interest rates. By June 2003, the federal funds rate stood at a mere 1%—an almost 45-year low.

- Accessibility of Cheap Credit: With such low rates, borrowing became extremely cheap. Financial institutions, enticed by the possibility of increased lending, began to relax their standards. Mortgages, which had previously been the reserve of the financially secure, became accessible to a broader population, including those with dubious creditworthiness. This influx of buyers into the market, armed with easy-to-obtain credit, was one of the foundational pillars of the housing boom.

- Innovative and Risky Financial Products: With cheap credit widely available, financial institutions grew innovative, devising new ways to lend. The era saw the proliferation of subprime mortgages, adjustable-rate mortgages, and “NINJA” (No Income, No Job, and No Assets) loans. These high-risk lending practices were premised on the belief that housing prices would continue their upward climb, ensuring that even high-risk borrowers could refinance or sell if they faced difficulties in repayment.

- Securitization: Not only did banks lend to high-risk borrowers, but they also bundled these loans into mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) which were then sold to investors globally. The belief was that these instruments, backed by real estate, were solid investments. This spread the risk across the global financial system, turning a housing crisis into a global financial meltdown when things went south.

As we now know, this cocktail of low-interest rates, risky lending, and financial innovation, while initially stimulating growth, set the stage for the Great Recession.

The Importance of Global Economic Factors

- Interconnected Financial Markets: The 21st century has ushered in an era of profound financial interconnectedness. An economic ripple in one part of the world can swiftly become a wave elsewhere. The U.S. housing bubble’s burst wasn’t just an American crisis; it led to a domino effect, impacting financial institutions worldwide that had invested in U.S. real estate through MBS and CDOs.

- Trade and Investment Flows: Global economic factors like trade balances, foreign direct investment, and cross-border lending can have a profound impact on housing markets. For instance, a surge in foreign investment can significantly drive up housing prices in specific cities or regions.

- Global Supply Chains: A disruption in one part of the world can impact the availability and cost of building materials elsewhere, affecting construction rates and housing prices.

- Migration Patterns: Global political or economic crises can lead to migration surges, affecting housing demand in regions experiencing a high influx of refugees or migrants.

The housing market, though rooted in local soil, is influenced by winds that blow from every corner of the globe. For stakeholders, recognizing the broader global context—understanding how external stimuli can ignite, fuel, or extinguish a housing boom—is crucial. The lesson is clear: in an interconnected world, a myopic view of housing markets can be perilous. Instead, a holistic understanding, one that factors in both local nuances and global dynamics, is imperative.

source: Slidebean on YouTube

Lesson 2: Bubbles Can Be Fueled by Speculation

At its core, speculation involves making high-risk investments with the hope of substantial returns. When speculative behavior takes root in housing markets, it can significantly distort the fundamental dynamics of supply and demand, transforming homes—often seen as stable, long-term assets—into volatile commodities. The impacts of such behavior are profound and often destructive.

Japan in the 1980s: The Zenith of Speculative Frenzy

The story of Japan’s housing and land bubble in the late 1980s serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked speculation. This period, often referred to as the “Bubble Economy,” witnessed a confluence of factors that set the stage for rampant speculation:

- Easy Credit Policies: Japan’s central bank maintained low-interest rates, making borrowing relatively cheap. This policy was aimed at combating the appreciation of the yen but inadvertently made it easier for businesses and individuals to take on significant debt.

- Cultural Belief in Land Value: In Japan, land has traditionally been viewed as a precious asset due to its scarcity, especially in urban areas. This cultural perspective amplified the belief that land values would perennially rise.

- Corporate Speculation: Unlike many other housing bubbles dominated by individual speculators, corporations played a major role in Japan. Businesses began investing heavily in real estate, not just for operational needs but as speculative assets.

By the height of the bubble, prices were astronomical. Some estimates suggested that the Imperial Palace’s grounds in central Tokyo were worth more than all of the real estate in California.

However, when the bubble burst in the early 1990s, Japan entered a prolonged economic downturn, often termed the “Lost Decade,” from which it took years to recover. Real estate values plummeted, leaving many with assets worth a fraction of their peak value.

Spain in the Early 2000s: A Speculative Fiesta

Spain’s housing bubble, which began in the late 1990s and peaked in the mid-2000s, offers another stark example of speculative fervor. Key elements driving this bubble were:

- Eurozone Entry: Spain’s entry into the Eurozone in 1999 gave it access to low-interest rates, significantly lower than what the country was historically used to. This led to an explosion of mortgage lending.

- Construction Boom: Spain saw a construction bonanza. By 2007, Spain, with 40 million people, was building as many homes as Germany, France, and the UK combined, countries with a combined population of over 200 million.

- Speculative Buying: Many Spanish residents, witnessing the rapid appreciation in home values, invested in second homes or even multiple properties, hoping to sell them at a profit. This speculative buying further inflated prices.

- Foreign Investment: The sun-soaked coasts of Spain attracted foreign buyers, many of whom were speculating on vacation homes’ rising value.

The aftermath of the bubble’s burst was severe. Spain faced skyrocketing unemployment rates, especially in the construction sector, and many banks teetered on the brink of collapse, necessitating international bailouts.

Impact of ‘Flipping’ and Speculative Buying on Housing Prices

- Artificial Demand: Speculative buying, especially “flipping” (buying properties to sell them quickly at a profit), creates a surge in demand that isn’t based on genuine housing needs. This artificial demand drives up prices.

- Distortion of Supply Dynamics: Responding to increased demand, builders may ramp up construction. When speculation wanes, markets can be left with an oversupply of properties, leading to plummeting prices.

- Barrier to Genuine Homebuyers: Speculatively driven price increases can push homes out of reach for many genuine homebuyers, turning housing markets into investors’ playgrounds and sidelining those looking for a home to live in.

While speculation might seem like a pathway to quick profits, its broader impacts can be devastating for economies and individuals. Housing markets driven by speculation can rapidly disconnect from economic realities, leading to bubbles that, when burst, leave lasting scars on societies and economies. Recognizing and curbing speculative behavior is crucial for maintaining healthy, stable housing markets.

Lesson 3: Over-reliance on Rising Property Values Can Be Detrimental

One of the most pervasive beliefs during a housing bubble is that property values will continue to rise indefinitely. This assumption, though comforting, can lead to systemic vulnerabilities. When entire economies and personal financial decisions hinge on perpetual growth in property values, the eventual correction or crash can be all the more devastating.

The U.S. Belief that Home Prices Would Always Rise: A Deep Dive

In the years leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, the U.S. housing market became a bedrock of optimism. This was not just a baseless belief; historical data seemed to back it up. For many decades, barring a few minor hiccups, U.S. property values had largely seen an upward trajectory.

- Historical Context: Homeownership has long been embedded in the American dream. Coupled with post-WWII policies encouraging homeownership and tax incentives favoring property acquisition, there was strong national sentiment towards buying homes. Over the years, as property values increased, this sentiment transformed into a belief that investing in real estate was a ‘sure bet’.

- Subprime Confidence: This deep-rooted belief facilitated the rise of subprime mortgages. Even individuals with low creditworthiness were granted mortgages under the assumption that, if they defaulted, the underlying property could be sold at a profit due to continually rising prices.

- Home Equity Loans: As property values rose, many homeowners tapped into their homes’ increasing equity, taking out second mortgages or refinancing to cash out their equity. This money was often used for consumption or investment in more real estate, further inflating the bubble.

- Risk Diffusion through Securitization: Mortgage lenders, buoyed by the belief in ever-rising property values, felt comfortable selling these mortgages to investment banks. These banks then bundled them into complex financial instruments, which were sold globally. The underlying notion was that these securities were rock-solid because they were backed by real estate, an asset believed to be perpetually appreciating.

Dangers of Basing Financial Decisions on Perpetual Growth

- Overleveraging: If individuals and institutions believe that property values will invariably rise, they might take on excessive debt, assuming that future property value increases will cover their liabilities. This overleveraging makes them vulnerable to any downturn in property values.

- Complacency in Risk Assessment: The belief in eternal growth can lead to lax lending standards, as we saw with the proliferation of NINJA loans (No Income, No Job, No Assets) in the U.S. The assumption is that rising property values will cover any potential defaults, leading lenders to neglect traditional risk assessment metrics.

- Misallocation of Resources: When a society collectively believes that one sector, like real estate, is a surefire winner, resources (both financial and human) can be disproportionately funneled into that sector. This can lead to neglect of other potentially more productive areas of the economy.

- Economic Vulnerability: When a large portion of an economy’s growth is predicated on perpetually rising property values, any stagnation or decline in that sector can lead to widespread economic downturns, as the U.S. witnessed in 2008.

- Individual Financial Ruin: On a personal level, basing significant financial decisions, like retirement planning, on ever-rising property values can lead to personal financial crises when the market corrects.

While it’s tempting to base decisions on past performance and optimistic forecasts, an overreliance on the belief that property values will eternally rise is fraught with danger. It’s a stark reminder that diversification, prudent risk assessment, and skepticism towards too-good-to-be-true scenarios are essential in both personal and national financial planning. The belief in endless growth, despite its appeal, can sow the seeds of profound financial instability.

source: EconClips on YouTube

Lesson 4: Government Policies Can Inadvertently Contribute

Governments, in their quest to stimulate economic growth, promote homeownership, or achieve other socio-economic goals, can sometimes implement policies that inadvertently stoke the fires of housing bubbles. While the intentions behind these policies might be noble, the unintended consequences can be grave, turning short-term boons into long-term banes.

How Tax Incentives and Lending Policies Can Exacerbate Bubbles

- Tax Incentives: By offering tax breaks or deductions related to property ownership or investment, governments can stimulate demand. While this might increase homeownership rates or stimulate construction in the short term, it can also fuel speculative buying, leading to an overheated market.

- Loose Lending Policies: Governments, especially in developing economies or in post-recession scenarios, might encourage banks to lend more freely to boost economic activity. This can result in a flood of cheap credit, feeding into a housing bubble.

- Subsidies and Grants: Direct financial incentives, like grants for first-time homebuyers, can lead to increased demand, pushing up prices, especially if supply doesn’t keep pace.

- Zoning and Land-Use Regulations: Restrictive land-use policies can limit the supply of new housing, even in the face of rising demand, leading to rapid price appreciation. On the other hand, too lax policies can cause overconstruction and eventual market saturation.

- Government Guarantees: When governments provide guarantees on certain types of loans or backstop certain financial institutions, it can lead to moral hazard. Lenders, believing they have a safety net, might indulge in riskier lending practices.

Ireland’s Property Tax Incentives in the 2000s: A Case in Point

The Celtic Tiger, as Ireland was known during its rapid economic growth phase in the late 1990s and early 2000s, offers a poignant illustration of how government policies can inadvertently contribute to housing bubbles.

- Background: Ireland’s growth was spectacular, with GDP growth rates often exceeding 6% annually. This economic boom was accompanied by a surge in property prices.

- Tax Incentives: The Irish government introduced a range of tax incentives to stimulate property development, including tax breaks for building rental properties and urban renewal projects. While these policies were initially aimed at addressing genuine housing and urban development needs, they soon started feeding speculative development.

- Impact on Construction: Encouraged by these incentives and the general economic optimism, construction boomed. By the mid-2000s, construction-related activities accounted for almost a quarter of Ireland’s GDP, an unsustainably high proportion.

- Fueling the Fire: The tax incentives, coupled with loose lending practices by Irish banks, created a potent mix. Many people started buying second homes or investing in properties under development, expecting to benefit from both the tax breaks and anticipated price appreciation.

- The Crash: When the global financial crisis hit in 2008, Ireland’s property bubble burst dramatically. Property values plummeted, many developments remained unfinished, and the banking sector, heavily exposed to real estate, required significant bailouts. The aftermath saw Ireland grappling with severe economic contraction and soaring unemployment.

In retrospect, while the Irish government’s intentions were to stimulate growth, urban renewal, and housing accessibility, the policies put in place inadvertently turned the property market into a speculative frenzy. This serves as a lesson that government interventions, no matter how well-intentioned, need to be carefully calibrated and frequently reassessed to ensure they don’t lead to market distortions or bubbles.

Lesson 5: Lending Standards Matter

Lending standards form the backbone of a stable financial and property market. When these standards are compromised, either due to aggressive growth strategies, lax regulatory oversight, or misplaced optimism, the consequences can be far-reaching. Proper checks and balances in lending practices are crucial not just for individual borrowers and lenders, but for the health of the broader economy.

The Risk of Subprime Lending and Lack of Proper Checks

- Defining Subprime Lending: At its core, subprime lending refers to the practice of lending to borrowers who do not meet the typical criteria for a prime loan, often because of a lower credit score, limited credit history, or other financial challenges. Such loans usually come with higher interest rates to compensate for the increased risk.

- Short-term Gains, Long-term Pains: For banks and lenders, there’s an allure to subprime lending. The higher interest rates mean more substantial profits, and during housing booms, the perceived risk is often diminished by the belief in ever-rising property values. However, when the tide turns, these loans are often the first to default, causing cascading problems for the financial sector.

- Moral Hazard and Misaligned Incentives: Lenders, especially when driven by commission-based models, may have incentives to approve subprime loans without due diligence. This situation is further exacerbated if these loans are then sold to third parties or bundled into securities, thus offloading the risk from the original lender.

- Financial Domino Effect: Subprime loans, due to their inherent risk, have a higher likelihood of leading to foreclosures. A surge in foreclosures can flood the market with properties, leading to rapid declines in property values and, subsequently, a broader financial meltdown.

The U.S. Subprime Mortgage Crisis: A Catastrophic Tale

The subprime mortgage crisis in the U.S. during the mid to late 2000s is a textbook example of the dangers of compromised lending standards.

- Origins: With the U.S. housing market booming in the early 2000s, there was a rush to provide mortgages to as many consumers as possible. Financial institutions began offering loans to subprime borrowers, often with adjustable rates that started low but could rise significantly over time.

- Financial Engineering: Many of these subprime mortgages were then bundled together and converted into complex financial products called mortgage-backed securities (MBS). These were sold globally to investors seeking higher yields.

- Crisis Unfolds: As adjustable rates began to reset at much higher levels, many borrowers found themselves unable to make payments. Foreclosures surged. The mortgage-backed securities, now tainted with bad loans, began to plummet in value, causing massive losses for global financial institutions.

- Global Ramifications: Due to the interconnectedness of global finance, the subprime crisis didn’t stay contained within the U.S. Financial institutions around the world, having invested in these securities, faced significant losses. This led to a global credit crunch, where trust in the financial system eroded, and lending between institutions froze.

- Bailouts and Recession: With major banks and financial institutions on the brink of collapse, governments worldwide had to step in with bailouts. The U.S. saw the largest bailout in its history with the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act in 2008. The global economy entered a severe recession, with millions losing jobs, homes, and savings.

The U.S. subprime mortgage crisis is a stark reminder of the dangers of lax lending standards. It underscores the importance of maintaining rigorous checks and balances in the lending process, ensuring that both borrowers and lenders understand and can manage the associated risks. This crisis was not merely a failure of individual institutions but a systemic failure, highlighting the need for vigilant oversight, transparency, and accountability in the financial system.

Lesson 6: The Ripple Effect on the Broader Economy

The health of the housing market is often deeply intertwined with the broader economy. A significant disruption in this sector can send shockwaves throughout various industries, affecting employment, consumer spending, investment, and even global trade. Understanding these linkages underscores the importance of monitoring and managing housing bubbles before they burst.

How a Housing Market Crash Can Lead to Broader Economic Downturns

- Banking and Financial Sector Stress: The housing market’s health is closely linked to the banking sector due to mortgages. A housing market crash can lead to a rise in defaults, affecting banks’ balance sheets and potentially leading to bank failures.

- Reduced Consumer Spending: As housing prices drop, homeowners feel less wealthy and may cut back on spending, impacting industries ranging from retail to services.

- Slump in Construction and Related Industries: A housing market downturn can lead to reduced demand for new homes, affecting construction jobs, and industries that supply materials and services to builders.

- Impact on Small Businesses: As consumers cut back on spending and banks become more cautious with lending, small businesses can struggle to secure financing or face decreased sales, leading to layoffs or closures.

- Global Impact: In an interconnected global economy, a downturn in one major country’s housing market can affect international trade, global financial markets, and foreign investments.

The Great Recession and its Global Effects: A Cascading Crisis

The Great Recession that began in 2007-2008 offers a vivid illustration of how a housing market crash, originating in one country, can have a domino effect on the global economy.

- Origins in the U.S. Housing Market: As discussed earlier, the subprime mortgage crisis in the U.S., spurred by falling housing prices and rising mortgage defaults, was the spark that ignited the Great Recession.

- Banking Crisis: Major banks and financial institutions, burdened by bad loans and toxic assets linked to the housing market, faced severe stress. Iconic institutions like Lehman Brothers collapsed, while others required massive government bailouts to stay afloat.

- Global Contagion: The crisis rapidly spread beyond the U.S. borders. European banks, having invested heavily in American mortgage-backed securities, faced significant losses. Countries like Iceland saw their entire banking system collapse, while others like Ireland, Spain, and Greece grappled with deep financial crises.

- Worldwide Economic Downturn: The banking crisis led to a credit crunch, where lending and borrowing between institutions dried up. This impacted businesses worldwide, leading to reduced investment, layoffs, and reduced consumer spending. The global economy contracted, with countries from Japan to Brazil feeling the pinch.

- Policy Responses: Governments worldwide responded with a combination of monetary easing, fiscal stimulus, and bailouts. Central banks slashed interest rates, and governments pumped money into their economies to stimulate growth. While these measures helped stabilize the situation, they also led to long-term challenges like rising national debts.

- Social and Political Ramifications: The Great Recession wasn’t just an economic crisis. High unemployment, austerity measures, and financial stress led to social unrest in many countries. This period also saw a rise in populist and anti-establishment sentiments, shaping the political landscape in many regions for years to come.

The Great Recession underscores how interconnected the modern global economy is. A disruption in one sector, like housing, in one country can rapidly escalate into a global crisis. It serves as a potent reminder that vigilant oversight, international cooperation, and sound economic policies are crucial in an increasingly interconnected world.

Lesson 7: Early Warning Signs Are Often Overlooked

Housing bubbles, despite their profound impact, don’t emerge out of thin air. They develop over time, often presenting a series of warning signs. However, these signals can be easily overlooked, dismissed, or rationalized due to a variety of reasons, from cognitive biases to economic pressures. Recognizing and acting upon these early indicators is crucial for preemptive action.

Cognitive Biases that Play a Role

- Optimism Bias: This refers to the tendency for individuals to believe that they are less at risk of experiencing negative events compared to others. In the context of a housing bubble, this can manifest as a belief that “this time is different” or that one’s investments are somehow safer than those of others.

- Herd Behavior: This is the phenomenon where individuals follow the majority in thoughts, opinions, and behaviors. In booming housing markets, as more and more people invest, others follow suit, fearing they might miss out on potential gains. This behavior can further inflate prices and exacerbate bubbles.

- Confirmation Bias: This is the tendency to search for, interpret, and remember information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions. For instance, during a housing boom, bullish investors might only focus on positive news and forecasts, ignoring contradictory evidence or warning signs.

- Overconfidence: Some investors or market players might believe they can always “time the market” or predict its movements better than others. This overconfidence can lead to riskier investment decisions and amplify market volatility.

Real-world Examples of Ignored Warning Signs in Housing Markets

- The U.S. Prior to 2008: In the lead-up to the housing crash, there were numerous indicators of an overheating market. These included skyrocketing housing prices detached from fundamental values, a surge in subprime lending, and an increase in house flipping. Yet, many experts, investors, and even policymakers dismissed these signs, often citing innovative financial products or a “new economic paradigm” as reasons the boom would continue.

- Spain’s Property Bubble: Before the financial crisis, Spain experienced a massive property boom. By 2007, the country was constructing more homes than Germany, France, and the UK combined. Warnings, such as a sudden increase in vacant new properties and an over-reliance on construction for employment, were often downplayed or overlooked.

- Japan in the Late 1980s: Japan’s property and stock market bubble of the late ’80s saw astronomical valuations. At one point, the land under the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was said to be worth more than the entire state of California. Despite such glaring indicators, many believed in the unique strength and resilience of the Japanese economy, dismissing concerns until the bubble burst, leading to a prolonged economic stagnation.

- Australia’s Persistent Warnings: Over the last couple of decades, various experts have periodically warned of an Australian housing bubble, pointing to signs like high house price-to-income ratios, elevated household debt, and speculative buying. While a catastrophic crash hasn’t materialized as of the last update in 2021, these consistent warnings underscore the challenges of interpreting and acting upon market indicators in real-time.

Many housing bubbles seem obvious. Yet, in the moment, a combination of cognitive biases, economic interests, and sometimes even regulatory oversights can lead to collective blindness. To safeguard against future bubbles, it’s vital to cultivate a culture of vigilance, critical analysis, and, crucially, humility about the limits of our predictive powers.

Lesson 8: Bubbles Can Have Lasting Societal Impacts

While the immediate economic consequences of housing bubbles are often the focus of analysis and discussion, the societal ripples can be just as profound, affecting generations of homeowners, renters, and entire communities. From altered life trajectories to reshaped neighborhood landscapes, the fallout from a housing bubble is more than just numbers on a balance sheet.

The Long-term Effects on Homeowners, Renters, and Communities

Homeowners:

- Negative Equity: Homeowners with mortgages can find themselves “underwater,” owing more than their property’s current value. This situation can lead to financial strain, mental stress, and limit their ability to move or refinance.

- Forced Moves: Defaulting on mortgages can lead to foreclosure, resulting in families being uprooted, often disrupting children’s education and severing community ties.

- Post-bubble Reluctance: The trauma of a housing crash can make individuals wary of re-entering the housing market, even when conditions stabilize.

Renters:

- Increased Rent: As housing prices rise during a bubble, so too can rents. This surge can displace long-term renters and make areas unaffordable for local residents.

- Decreased Stability: Renters in areas heavily affected by bubbles might experience less rental stability due to landlords facing financial strains or properties being sold off.

- Post-crash Opportunities and Risks: After a bubble bursts, while some renters might find opportunities to buy at lower prices, others might face challenges if rental properties are neglected or if local job opportunities diminish.

Communities:

- Shift in Demographics: Surging housing costs can alter the demographic makeup of a neighborhood, potentially pushing out long-term residents in favor of wealthier newcomers.

- Decline in Community Cohesion: Rapid turnover of residents and the influx of speculative or short-term investors can weaken community ties and reduce civic participation.

- Impact on Local Services: Reduced property values post-bubble can lead to decreased property tax revenues, affecting local services like schools, parks, and infrastructure.

Case Study: Foreclosures and Subsequent Neighborhood Decline Post-2008 in the U.S.

The 2008 financial crisis, rooted in the U.S. housing bubble burst, provides a poignant example of the lasting societal impacts of such events.

- Wave of Foreclosures: Following the crash, millions of Americans lost their homes to foreclosure. By some estimates, over 10 million homes were foreclosed upon between 2006 and 2014.

- Deserted Neighborhoods: In the hardest-hit areas, like parts of Florida, Nevada, and California, entire neighborhoods were left with vacant homes. This led to aesthetic decay, increased crime, and a reduction in property values for remaining homeowners.

- Social Fabric Erosion: With homes vacant and families displaced, the social fabric of many communities was eroded. Long-established networks of support, friendship, and community engagement were disrupted, with some areas taking years to recover, if at all.

- Impact on Children and Education: Children in foreclosed homes faced academic and social challenges, from changing schools frequently to dealing with the stress and stigma of losing their homes.

- Economic Polarization: Post-crisis, as the economy slowly recovered, many foreclosed homes were bought up by institutional investors and converted into rental properties. This shift often led to a more significant wealth divide, with former homeowners now renting, and large investors reaping the benefits of the subsequent rise in rental markets.

- Legacy of Distrust: The manner in which the crisis unfolded, from predatory lending practices to perceived inadequacies in government responses, left a legacy of distrust. Many Americans grew wary of banks, financial institutions, and even the mechanisms of homeownership itself.

Housing is more than just a financial asset; it’s a fundamental human need and often a cornerstone of one’s identity and sense of belonging. The societal impacts of housing bubbles, therefore, reverberate deeply, reminding us that the stakes in understanding and mitigating such events are immensely high.

Lesson 9: International Factors and Globalization Intensify Effects

The modern global economy is characterized by a complex web of interconnectedness. Trade, investment, and financial flows crisscross borders, and the rise of globalization over the past few decades means that economic developments in one country can have outsized effects on others. Housing markets, traditionally seen as localized sectors, are not immune to these global forces. The dynamics of international factors can both contribute to and amplify the effects of housing bubbles.

How Interconnected Global Economies Can Amplify Housing Bubbles

- Capital Flows and Investment: In a globalized world, capital seeks the best return, irrespective of borders. When a country’s housing market is perceived as booming, it can attract significant foreign investment, further driving up prices and inflating potential bubbles.

- Global Interest Rates: Central banks in major economies, like the U.S. Federal Reserve or the European Central Bank, influence global interest rates with their policies. Low-interest rates can spur borrowing and inflate asset prices, including real estate, across multiple countries.

- Contagion and Investor Sentiment: Negative developments in one country’s housing market can affect investor sentiment globally. Fear of a potential global downturn can lead to reduced investments and a pullback from risk, which can further depress housing markets worldwide.

- Interlinked Financial Institutions: Large global banks and financial institutions operate across borders. A crisis in the housing market of one country can affect the balance sheets of these institutions, potentially leading to credit crunches and reduced lending in other parts of the world.

- Supply Chain Effects: The construction industry relies on global supply chains for materials. A downturn in one major market can impact suppliers globally, potentially increasing costs and affecting housing markets in seemingly unrelated countries.

The Ripple Effects of the U.S. 2008 Crash on Europe and Asia

The 2008 housing market crash in the U.S. and the subsequent financial crisis offers a stark illustration of how interconnected the global economy has become.

- European Financial Institutions: European banks had heavily invested in U.S. mortgage-backed securities. As defaults rose in the U.S., these assets became toxic, leading to significant losses and even the collapse or nationalization of some banks, such as Northern Rock in the UK and Fortis in Belgium.

- Credit Crunch: The distrust between financial institutions post-crash led to a freeze in global credit markets. European businesses found it challenging to secure financing, leading to reduced investment and job losses.

- Iceland’s Complete Meltdown: Iceland’s banks had expanded aggressively overseas. The global credit crunch meant they couldn’t refinance their foreign debts, leading to the collapse of the country’s banking system and a profound economic and social crisis.

- Asian Export Economies: Countries in Asia, especially those reliant on exports like China and Japan, felt the pinch as Western consumer demand plummeted. While many Asian countries did not have housing bubbles of their own, the global economic downturn affected their export-driven economies, leading to factory closures and job losses.

- Emerging Markets: Countries like India and Brazil, which had been enjoying robust growth rates fueled by global investments, experienced sharp reversals as foreign capital fled to safer assets.

- Global Response: Central banks around the world coordinated responses, slashing interest rates, and injecting liquidity into markets. Governments also rolled out stimulus packages to boost demand and stave off deeper recessions.

In an era of globalization, the old adage that “when the U.S. sneezes, the world catches a cold” has never been truer. But it’s not just about the U.S.; disruptions in any major economy can have cascading effects. It underscores the importance of international cooperation, regulatory alignment, and vigilance in monitoring and managing global economic risks.

Lesson 10: Prevention and Regulation Are Crucial

In the world of finance, it’s often said that the next crisis won’t look like the last. However, while the specifics may differ, the underlying dynamics of exuberance, unchecked risk, and lack of oversight have recurred throughout history. It’s a reminder that proactive measures – both in terms of prevention and regulation – play a pivotal role in stabilizing housing markets and the broader economy. Such measures, if crafted thoughtfully and applied diligently, can ward off bubbles or at least mitigate their damaging effects.

Importance of Regulatory Frameworks to Prevent Unchecked Lending

- Learning from History: One of the stark lessons from past housing bubbles, such as the U.S. subprime crisis, is that lax lending standards can be catastrophic. Unregulated or poorly regulated mortgage markets can allow risky lending behaviors to proliferate.

- Consumer Protection: Strong regulatory frameworks prioritize consumer protection. They prevent predatory lending practices where borrowers might be coaxed into loans they can’t afford or don’t understand.

- Financial System Stability: Beyond protecting individual homeowners, robust regulations are critical to maintaining the overall health and stability of the financial system. By setting capital requirements and overseeing lending practices, regulators can ensure that banks remain solvent even if some loans go bad.

- Transparency and Information: Adequate regulations mandate transparency, ensuring that borrowers fully understand the terms of their loans. This helps in making informed decisions and reduces the chances of defaults.

- Flexibility: Good regulation is not about being overly restrictive but being flexible and adapting to changing market conditions. Regulatory bodies need to review and adjust policies in light of new financial products, market dynamics, and emerging risks.

The Role of Central Banks and Fiscal Policies in Managing Housing Markets

- Interest Rate Management: Central banks wield a powerful tool in the form of interest rates. By raising or lowering rates, they can influence borrowing costs. Higher rates make borrowing more expensive, potentially cooling an overheated housing market, while lower rates can stimulate activity.

- Macroprudential Policies: These are measures central banks can use to address systemic risks in the financial system. For instance, by setting limits on how much banks can lend relative to a property’s value or a borrower’s income, they can mitigate the risks of bubbles.

- Liquidity Provision: In times of crisis, central banks can step in as lenders of last resort, providing liquidity to financial institutions to prevent a complete meltdown, as seen during the 2008 financial crisis.

- Fiscal Policies: Government fiscal policies can also influence housing markets. Tax incentives, such as mortgage interest deductions or property tax breaks, can stimulate demand. Conversely, introducing property taxes or reducing tax benefits for speculative property investments can dampen excessive price growth.

- Housing Policies: Governments play a direct role in housing through policies related to public housing, rent controls, and housing grants. Such policies can have significant impacts on housing supply and demand dynamics.

- International Coordination: Given the globalized nature of modern finance, coordination between central banks and regulatory bodies across countries is crucial. Sharing information, aligning policies, and jointly responding to global challenges can be more effective than countries acting in isolation.

While no regulatory framework can guarantee immunity from housing bubbles, the importance of sound, proactive governance in the housing and financial sectors cannot be overstated. By learning from past mistakes and continuously adapting to new challenges, regulators and policymakers can play a crucial role in ensuring that housing markets serve their fundamental purpose – providing safe, stable, and affordable homes – without becoming the epicenter of financial crises.

Conclusion: Housing Bubbles

The cyclical ebb and flow of economies, sectors, and markets, paired with the interplay of human psychology, policies, and external factors, have seen the rise and fall of many housing bubbles throughout history. These bubbles have not only impacted individual homeowners and investors but have reverberated through global economies, leaving lasting impacts on societies, financial systems, and governance models. The lessons gleaned from these historical events are not just academic footnotes but crucial guideposts as we navigate an ever-complex, interconnected world.

The Recurring Nature of Housing Bubbles and the Need for Vigilance

- Historical Patterns: The history of housing bubbles is testament to the fact that they have occurred with a disconcerting regularity across different countries and eras. While the triggers and specifics might differ, the underlying patterns of rapid price escalation, exuberant investor sentiment, and eventual painful corrections remain consistent.

- The Role of Human Behavior: At the core of these patterns is human behavior. From the optimism that fuels a market’s rise to the panic that ensues during its fall, our collective actions play a significant role. Cognitive biases like herd behavior, overconfidence, and the fear of missing out can exacerbate market swings.

- Evolving Complexity: The modern financial landscape, with its intricate financial instruments, globalization, and technological advancements, adds layers of complexity. While innovations can foster growth and benefits, they can also introduce new risks and amplify old ones. The 2008 financial crisis, with its labyrinthine web of derivatives and securitized mortgages, stands as a poignant example.

Emphasis on Learning from History to Prevent Repeating Mistakes

- Harnessing the Past: Each bubble, with its unique set of circumstances, offers insights. By meticulously studying them, policymakers, financial institutions, and even individual investors can better recognize the warning signs and act accordingly.

- Institutional Memory: One of the challenges in preventing recurring bubbles is the fading of institutional memory. As time distances us from the pain of the last crisis, complacency can set in. Thus, maintaining a robust institutional memory, through records, case studies, and continued education, is vital.

- Adaptive Regulation: Regulations shouldn’t be static. They need to evolve with the times, adapting to new financial products, changing market dynamics, and emerging risks. Continuous reviews, stress tests, and policy adjustments can keep the system resilient.

- Empowered Public: An informed and educated public can act as a counterbalance to market excesses. Financial literacy initiatives, transparent information dissemination, and consumer protection measures can empower individuals to make informed decisions.

- Global Collaboration: In a globalized world, housing bubbles in one country can have repercussions elsewhere. International cooperation, data sharing, and coordinated policy responses can bolster global financial stability.

In sum, housing bubbles and their subsequent bursts have taught us time and again the importance of vigilance, preparation, and adaptability. The scars left by these events serve as potent reminders of the potential devastation that can ensue when unchecked optimism meets flawed systems. As we look to the future, our best defense is a profound respect for history, an unwavering commitment to learning, and a collective resolve to chart a course that is both prosperous and stable. After all, those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it.

Important Information

Investment Disclaimer: The content provided here is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, tax or professional advice. Investments carry risks and are not guaranteed; errors in data may occur. Past performance, including backtest results, does not guarantee future outcomes. Please note that indexes are benchmarks and not directly investable. All examples are purely hypothetical. Do your own due diligence. You should conduct your own research and consult a professional advisor before making investment decisions.

“Picture Perfect Portfolios” does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy of the information in this post and is not responsible for any financial losses or damages incurred from relying on this information. Investing involves the risk of loss and is not suitable for all investors. When it comes to capital efficiency, using leverage (or leveraged products) in investing amplifies both potential gains and losses, making it possible to lose more than your initial investment. It involves higher risk and costs, including possible margin calls and interest expenses, which can adversely affect your financial condition. The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of anyone else. You can read my complete disclaimer here.